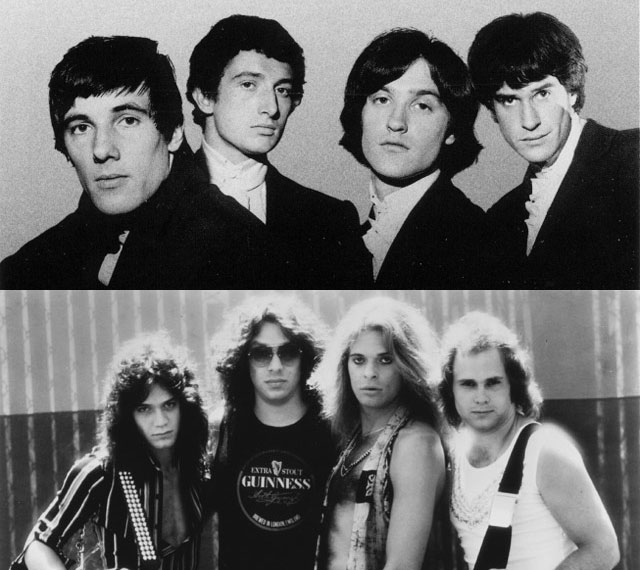

The Van Halen News Desk recently spoke to The Kink’s Dave Davies, who shared with us what he thinks of Van Halen’s cover versions of two of their original songs. Those of course are “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” and the classic “You Really Got Me,” which features one of the definitive riffs in all of rock and roll.

By VHND contributing writer, Kevin Dodds, author of Edward Van Halen: A Definitive Biography

Listen: The Kinks – You Really Got Me (1964)

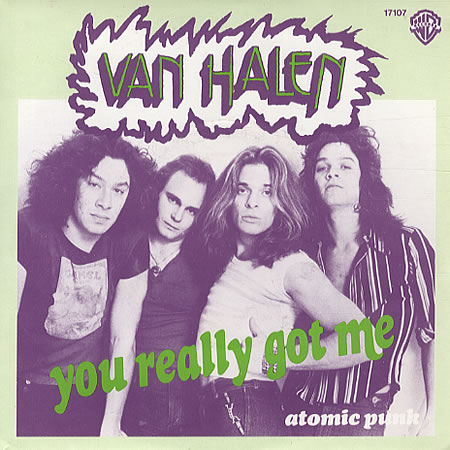

Listen: Van Halen – You Really Got Me (1978)

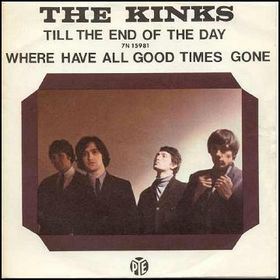

Every Van Halen fan knows why The Kinks are landmark in the VH legacy. “You Really Got Me” is a critical part of Van Halen’s radio and live repertoire—perhaps the one song that the band has performed the most. And, in an odd way, Van Halen essentially secured partial ownership of the song.

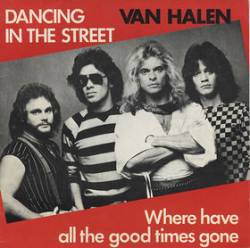

“You Really Got Me” is synonymous with Van Halen. The fact that it is coupled with “Eruption” on record, and now on the radio, makes it an even more vital component of Van Halen’s catalog. But it’s not a Van Halen song. However, you have never heard David Lee Roth introduce the song as a Kinks song. If that wasn’t odd enough, Van Halen not only returned directly to The Kinks for inspiration on Diver Down, they made their cover of The Kinks’ “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” the first track on that album.

“You Really Got Me” is synonymous with Van Halen. The fact that it is coupled with “Eruption” on record, and now on the radio, makes it an even more vital component of Van Halen’s catalog. But it’s not a Van Halen song. However, you have never heard David Lee Roth introduce the song as a Kinks song. If that wasn’t odd enough, Van Halen not only returned directly to The Kinks for inspiration on Diver Down, they made their cover of The Kinks’ “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” the first track on that album.

Dave Davies of The Kinks is the man who sliced the speaker cone in his “little green amp” with a razor blade to get the incredible distorted sound found in the critical electric guitar lines of the original “You Really Got Me”—and a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductee (class of 1990). The Kinks are almost as famous for their music as the rocky relationship between Dave and his brother, Kinks lead singer Ray Davies. In the past, Dave has been quoted as saying unflattering things about Van Halen, but those can all be set aside now.

I was fortunate to secure Dave for a telephone interview on Thursday, October 24, 2013. He was gracious enough to give me nearly an hour of his time to discuss in great detail: the origins and impact of “You Really Got Me,” the influence of The Kinks on Van Halen, the effect of Van Halen’s covers on The Kinks, and Dave’s full thoughts on all of Van Halen’s Kinks work.

Kevin Dodds (Austin, TX): What’s your experience been like recording and releasing your 2013 solo album I Will Be Me?

Dave Davies (New York City, NY): I had such a ball making it. It took me about two years to make it and took about a year to write it. I wanted to try and keep it fairly raw. Keep a lot of edge in it and the flaws in there, and the guitar is quite prominent. I really enjoyed writing the songs and getting the arrangements together. It covers a lot of different topics at length. I wanted to write something about “You Really Got Me,” and there’s a track called “Little Green Amp,” and the guitar riff is “You Really Got Me” backwards. I just thought it would be funny to sing a song about “You Really Got Me” that wasn’t really “You Really Got Me,” but that was about that time and the emotions that were surrounding people. So, the theme itself was backward. That was funny.

How are things going on the Rock N Roll Journey film project?

Oh, good. We did some filming in London recently. My son, Martin, is a filmmaker, editor, and researcher, and we’ve got quite a bit in the can, you know, some archival footage. It’s coming good, it’s really exciting.

Have you started filming current footage for the project?

Not yet. We’re doing some gigs coming up in New York next month [November 2013], and we’re going to Chicago, doing a few nights up there. We’ll film what we can—film a little bit of the city and the streets. It should be fun. I’m looking forward to it.

I was going to ask what it’s like working with your son on the film.

We’ve worked on a film before called “Mystical Journey,” which is more about The Kinks, and traveling, and mainly about my spiritual journey. But this is a different film. It will be more about people I’ve known in the business and interviews with people from back in the day. Also, what I’m doing currently, some live footage, talking with fans, and what have you. It’s our second project together. I mean, on the first project, all we did was argue! [Laughs.] Martin’s got very strong views about what he wants and I’ve got very strong views about what I want!

He’s a Davies, huh?

[Laughs heartily.] Yeah! Sure he is.

You saying that made me want to mention to you that Eddie Van Halen’s son Wolfgang is now the bass player in Van Halen. Were you aware of that?

That’s cool, I didn’t know that. Isn’t that cool?!

He’s been in the band since he was fifteen—since 2006.

Well, good for him! Keep his dad on his toes.

A funny thing that’s similar between The Kinks and Van Halen is that there are two brothers in the band. You and Ray, and in Van Halen, it’s Eddie and Alex Van Halen.

How’s it working out with them?

It’s going great, I think. They did a tour last year, and they played Australia—

But the brothers, do they get on? Or—?

Oh—yes. Alex and Eddie, they do get along. They’re really tight. They immigrated to America from the Netherlands together.

Ah, right. That’s where the name came from. That’s funny because my son, Daniel, he has a band called Yearlong Disaster, and we’re going to do some heavy rock tracks together for the band. And his email is Daniel “Van” Davies. It’s funny, it’s good working with your kids.

Before we get into “You Really Got Me,” what in the world made you use fifth chords [or power chords] back in ‘64? It was essentially unheard of before that.

Well, how I learned to play was I didn’t study music, I just picked it up. Even when we were listening to bands like The Ventures and trying to copy their playing, I mean when we were really young, me and Ray. I would listen to it and try and copy the melody, let’s say “Walk, Don’t Run” or something. That’s The Ventures, right?

Yes, it is.

Good. But I always copied it wrong and so it sounded different. But then as the years went by, I realized they called it improvisation. [Laughs.] So, I thought, “You can do anything, you can just try anything, just hope nobody notices!” I think to a degree, that certain element of rock and roll I think is really important. Those times when you’re not sure what the hell you’re going to do, and you might get lucky, and make happy accidents, you know? That to me is the essence of rock and roll.

I think the absence of the third in that fifth chord is what makes it so solid sounding.

One interesting thing I’ve learned, because I wasn’t a trained musician, I didn’t know what thirds and fourths and augmented sevenths—I didn’t have a clue what they were. I’m not so sure I do now! [Laughs.] What was really great—and I learned that from The Ventures—the rhythm guitar player was really good because he didn’t play all the strings always—sometimes he would just play the last three strings of each chord, which really is kind of like a bar chord. So, I noticed that you can use just those three fingers and don’t have to worry about sevenths, eighths, or even majors and minors, and I thought, “This is great!”

I have to tell you—and it’s an incredible coincidence—but when Eddie Van Halen was growing up in Southern California there in the mid-60s, surf rock was huge.

Oh, right.

It [surf music] was actually invented in Corona out by the Fender guitar factory east of Los Angeles, so, they were heavily influenced by that. Alex Van Halen—the first song he ever learned to play on the drums was “Wipeout.”

Oh, right.

And Eddie Van Halen, the first song that he learned to play on electric guitar was “Walk, Don’t Run” by The Ventures.

Oh, now that’s giving me a chill. That’s strange.

He said the bar chord was the first thing that he learned. And he said, “Okay, once I learned it, I was like ‘Hey! Any position!’” And he just played the song’s E-D-C-B progression over and over.

Yeah, that’s really funny because that was a big thing. Me and Ray were big Ventures fans. And as part of the back story to “You Really Got Me,” when I’ve talked about it in interviews and reflected back on the song, and also the mixture of influences. I was really into all these older generation jazz players, and they always built a song up based on riffs, kind of like rock music. So, I’m thinking—buh-buh-buh-dah / buh-buh-buh-duh / buh-buh-bah-duh-dah. Those kind of riffy things that are very syncopated. I love syncopated rhythms. But also a big influence, there was a B-side, a Ventures B-side, it was a B-side of a subsidiary in England—I don’t know what it would have been here. There was a track called “No Trespassing.” You could tell the flavor of it—that they probably just wrote it to maybe get a B-side. You know? Which people used to do—maybe they still do it. In those days, it was “Oh, we need a B-side.” “Oh, we’ll just play something and stick something on there.”

There’s a great change in “No Trespassing.” There’s this strange little chord thing, I don’t know what you call it technically. You’d probably know when you hear it. When it goes to A-flat/A to the break, from the G, it does that shift, it does that wedge shift. And when I first heard that, I thought, “Fuck! What’s that?!” It’s like a jazz inflection, or it just takes you somewhere else. Play the record when you get a chance and listen to it. That I think kind of inspired a lot of the lines we used to build “You Really Got Me” with. Not in a conscious way, but when you think back of how a back story builds up—it’s a long event, you know?

This kind of leads into the next part, when you break “You Really Got Me” down, there’s a really important element in that and many other early Kinks songs, which is the band’s modal dynamics—something that Pete Townsend has said was specifically what he attempted to duplicate with The Who. When I say modal, I mean how “You Really Got Me” uses the same riff on A and G, and then to B and A, and then to D and E. It moves in a “modal” fashion. “All of the Day and All of the Night” and “Tired of Waiting” use those similar kinds of musical themes.

Yep. Pete has been very nice about the influence [of The Kinks]. He obviously listened to all of our records and was inspired by it. But it’s good if there’s anything, he took it somewhere else and it became his own. That’s the whole idea of how to create a style. It’s not really what you do—it’s the style you create with and the dynamic inspiration behind it. You always know when Pete Townsend’s playing, you know? It’s just a style. It’s not really a technique—it’s just him.

Is “No Trespassing” how you stumbled upon the modal formula? Because, again, no one was really doing anything like that.

It might have been, but not a conscious thing. But it was one of those moments where you think, “Shit?! What’s that?!” That kind of thing that really sticks.

Do you recall when you first heard Van Halen’s version of “You Really Got Me?”

Do you recall when you first heard Van Halen’s version of “You Really Got Me?”

Oh, yeah. I heard it on the radio when we were on the road or something. When was it out?

It was 1978.

It was quite early, anyway. I quite liked a lot of the kind of crash and jam—Dead Kennedys. I liked that kind of tail-end of the punk thing, which I found reminded me of when we had first started. When I heard the guys’ [Van Halen’s] version of it, I felt, you know, “This sounds really flashy.” But it depicted the era, didn’t it? In that it was in the era when stadium rock was big, and guitars were flashier, and tight trousers, and swanky. The original record was—our record, the original, because Van Halen’s is a cover [laughs]—we literally had one, ball-busting chance to make that record, otherwise it would’ve never gotten made. The record company fucked up the first recording, and they had echo all over the place. It was awful. Our manager gave us two hundred pounds to go in the studio to get it how we wanted to do it. So, I just sliced my own damn speakers—really basic stuff. When I first heard the sound of it, it was either shit or bust. It was like, you know, I had to do it, otherwise we were never going to get another session. I had no idea what I was going to do on the solo. I was really just cocky, and I just fucking played something. And that’s what happened.

Our version is very much about survival and kids trying to express themselves. It’s like “You Really Got Me” has that feeling of kids just trying to express themselves. You know, back then, if we wanted to date a girl, we just went up to her and grabbed hold of her. And you didn’t wine and dine, or court. It was just really fundamental, basic kind of things that young kids did at that time. And the music reflected our own culture and behavior. So, really, even though it’s the same song, there’s a cultural emphasis and there’s patterns in it.

There’s a chasm between the two versions. One’s about a comfortable, American urban life. And one is about a raunchy, desperate kind of survival instinct. I’m not saying it wasn’t a good record. It always makes you feel good when people are inspired by your work.

The highest that Van Halen’s version charted on the pop charts in the U.S. was only #36, but that album that it’s on [Van Halen] has sold over ten million copies.

That’s amazing, isn’t it? Wow. That’s unbelievable.

I watched a bit of your link of the guys doing an acoustic version of “You Really Got Me” last night. [From Van Halen’s “Downtown Sessions” in 2012.]

What did you think about that?

I thought it was interesting. Because when you trim it all down back to basics, it becomes a lot more honest, doesn’t it? And there’s only certain things you can do when it’s a very simplified approach. I enjoyed that.

Did you prefer that to their original version?

In a sense—in a way I did because it was a lot more kind of just relaxed and bit more sort of honest. You know what it’s like when you go into the studio and everyone’s so hyper, and everything has to be so wonderful. Well, sometimes it doesn’t, and maybe just simple and in-your-face is better than all the years we’ve all spent in the studio trying to knit-pick this, and trying to “Oh, I can do it better than that—let me try it again!” And all this stuff. I’ve always been of the mind that sometimes the first accidents or first takes are the best. And it might get more intricate as you overdub, you know, “I can fix this,” stick a few notes in there. But it’s the first things that have the impact, the emotion, and the edge and nervousness, I think.

And my feelings toward Van Halen’s version of [“You Really Got Me”], well, first I want to say about the acoustic version, that it seemed really strange for me in watching a band talk about a song in the same way that we would have talked about “You Really Got Me.” I thought that was really kind of a bit spooky, like as if it was their song. But it wasn’t, it was ours. But the emotions when they talked about it—when they said that they’d save it up ‘til the end, and that it was an impact song—those were the same sort of conversations that me and Ray would have in rehearsal. So, that was kind of a bit spooky. That kicked off their career and it was also the song we wrote that launched The Kinks. So, that was kind of a bit spooky.

In that sense, there’s a thin line between homage and obfuscation, or kind of a calculated—or uncalculated—attempt to establish some kind of ownership. Would you agree with that?

Yeah. I think when I first heard it, it sounded like someone trying to cash in on my own music, like get on my coattails with their music. But then they made it their own with Edward’s playing, which is so of that genre, of that era, which is special in its own right. That’s not cryptic—it’s just different. But my first feelings were that it was calculated, and kind of measured, and well-rehearsed. And the original record was just a bunch of kids doing it, thrown in the corner, and “Get on with this! You do it, or you’re out!”

I don’t know if you realize this, but Van Halen continues to play “You Really Got Me” at every single show over the past few years.

Isn’t that amazing?

What do you think about that? I think it speaks volumes about the song’s longevity.

Yeah, I think so. It’s a compliment. At the same time, I do smile to myself. [Laughs.] And yet another band that has made a prosperous career of listening to The Kinks. And that happened to many, many, many bands. And I feel glad that people use us as a source of inspiration. I mean even today, there’s kids that are like 13-14 sitting in their front rooms in London, or Manchester, or Denver even, and “Listen and try and copy this funny, little scruffy, original version.” [Laughs.]

It’s amazing that the song is almost fifty years old.

Yeah, next year is the fiftieth anniversary of “You Really Got Me” being on the charts in the U.K.

How in the world do you feel about that?

I don’t know, it’s strange. Because when you play the original record, you find it still has the same impact as yesterday. It could’ve been made this morning.

There’s no energy that wanes on that thing over the years. It’s the same.

Isn’t that amazing? I remember having that feeling when I first heard Chuck Berry and “Sweet Little Sixteen,” and when I first heard “Somethin’ Else” by Eddie Cochran, with that fizzy hi-hat. There is a power behind rock and roll—a spirit.

Edward did not want that song to be the band’s first single because it was a cover, but he had no leverage with Warner Brothers at the time because they were young and making their first record. Do you think they should have gone with an original tune first, or was their version of “You Really Got Me” just destined to be?

I don’t know, it’s curious. The record business is so weird—in those days it was even weirder. Because real artists had to virtually do what they were told or they’d never get a record out. And that happened to us, as well. I mean, we wanted to put certain records out, and the record company weren’t interested. But the difference is, because we had some sort of name, we’d put them out anyway. And then they would be considered flops or failures or bombs or whatever. But that has been a fundamental thing about The Kinks career, really. Up and down. Success, failure. But that kind of thing excites the music.

Who played the little piano part on that back in ‘64?

You know, I can’t remember. It could have been John Lord. And it might have been a session guy called Arthur Greensleeve, an old-school session pianist at the time.

It’s a really nice element of the recording. It’s subtle.

Yeah, we grew up listening to records that were using little rhythmic piano parts. You know that 50s rock thing, like Fats Domino and all those people. Those rhythmic parts. A lot of good rhythmic stuff wasn’t playable, it was just rhythmic. So, it really just takes you somewhere else. It’s so simple.

I think all great art, period, is about simplicity. It’s about innocence and self-expression and simplicity. And I think technique is great to have or you can’t do anything. I mean you can’t walk across the road if you don’t know to avoid the traffic. [Laughs.] If you know the music, it’s nice to get around to what you’re doing, I think. But a lot of musicians I think tend to get so insecure about what they can do that they bypass the simple stuff. They go way past it. And it’s hard to get back. I mean, when you think you know everything, where do you go? It’s very curious how people like Paul McCartney, the bass player, and he wrote such interesting melodies? He wasn’t a concert pianist. He was a bass player in a pop band. That’s really curious.

You had never heard Van Halen’s version of “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” until I sent it to you last week, is that correct?

You had never heard Van Halen’s version of “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” until I sent it to you last week, is that correct?

That’s right, yeah.

That was recorded just four years after “You Really Got Me,” and it was actually side-A, track number one on Van Halen’s 1982 album Diver Down.

Oh, wow!

As opposed to “You Really Got Me,” it’s a kind of a deep track, a deeper Kinks track. What did you think about their version of “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?”

Well, I liked it. The music—I felt happier with it than the “You Really Got Me” version. But there again, we’re talking about a chasm in difference culturally. “Where Have All the Good Time Gone?” we’re talking about reflecting back on an era in England that comes to a terrible war and a culture trying to rebuild itself. It had a cultural backstory to it, whereas the Van Halen thing is sort of a nostalgic reflection. But it’s still a good version, of course.

I think there was an irony there. The band was kind of on the verge of breaking up, and I think that “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” was a little tongue-in-cheek for them.

I think there was an irony there. The band was kind of on the verge of breaking up, and I think that “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” was a little tongue-in-cheek for them.

Oh, yeah, it speaks volumes.

When they released that version, Van Halen was tied to The Kinks forever. They had recorded two of your songs in just four years, but it was because of that that I got turned on to The Kinks. That same year in ’82, you guys hit it big on MTV, so kids like me bought Van Halen’s album and your album and your back catalog. Do you think there was a mutual benefit thing there?

Yeah, sure. One thing helped the other, I’m sure. Of course there was.

I have to tell you that the world could really use a Kinks reunion in 2014, so what address should I tell people to send your brother, Ray, mail to?

[Laughs.] Facebook! The Kinks Facebook page.

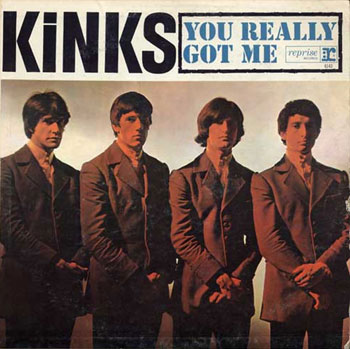

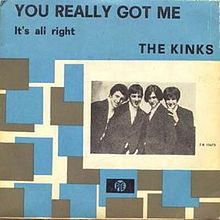

Did you know? The Kink’s “You Really Got Me” was released in the summer of 1964, during the height of the British Invasion, and reached Number 1 on the UK singles chart. It was later included on the Kinks’ debut album, Kinks.

“You Really Got Me” was an early hit song built around power chords (perfect fifths and octaves), and heavily influenced later rock musicians, particularly in the sub-genres heavy metal and punk rock. American musicologist Robert Walser wrote that it is “the first hit song built around power chords” while critic Denise Sullivan of Allmusic writes, “‘You Really Got Me’ remains a blueprint song in the hard rock and heavy metal arsenal.”

In 1999, “You Really Got Me” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. Rolling Stone magazine placed the song at number 82 on their list of the 500 greatest songs of all time and at number 4 on their list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time. In early 2005, the song was voted the best British song of the 1955–1965 decade in a BBC radio poll. In March 2005, Q magazine placed it at number 9 in its list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Tracks. In 2009, it was named the 57th Greatest Hard Rock Song by VH1.

Author Kevin Dodds published Edward Van Halen: A Definitive Biography, which is currently on sale for $10 off at Van Halen Store. Order it here.