This great piece was written by Dan Benbow for VHND and his own site, Truth and Beauty. Enjoy.

I was late to the party known as Van Halen.

Throughout most of their vintage period I listened to the Beatles, Stevie Wonder, top 40 radio. I saw the classic “Fair Warning” concert videos in the early ’80s on MTV, but the music didn’t stick; hard rock wasn’t yet part of my musical palette.

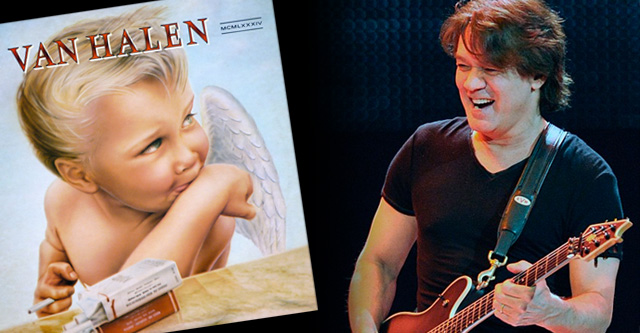

The gateway drug was “Jump,” Van Halen’s only number one record. Released as a single and a video at the tail end of 1983, the song opened my ears to the band.

By spring, “1984” was the high-adrenaline soundtrack that got my blood pumping before I walked out on the court as a freshman on the varsity tennis team. My doubles partner, a drummer on the side, had the bug too: he expertly mimicked Alex Van Halen in a pair of air band contests. The growing success of the album paralleled the excitement of a season in which we won the conference title.

By spring, “1984” was the high-adrenaline soundtrack that got my blood pumping before I walked out on the court as a freshman on the varsity tennis team. My doubles partner, a drummer on the side, had the bug too: he expertly mimicked Alex Van Halen in a pair of air band contests. The growing success of the album paralleled the excitement of a season in which we won the conference title.

By May, Van Halen was my favorite band. A cassette of “1984” or one of its five predecessors was in regular rotation on my $20 boom box. Filled with the zeal of the newly converted, I scrawled the boss Van Halen logo on notebooks, the inside of bathroom stalls, the back of desks, anywhere I had the time and space to spread the Gospel.

It wasn’t long before VH invaded my household. When we got our first family dog, I started calling the unnamed beagle Eddie. My parents initially agreed to the name as a placeholder only, but it ended up sticking.

That summer, my younger brother (at right) got in the act. With black hair, natural six pack abs, and boyish good looks, he was a fitting stand-in for Eddie Van Halen as he launched off our ottoman with a cardboard guitar. (Years later, he still had the bug, using “Panama” in a video shoot with his friends in Africa, shown here:)

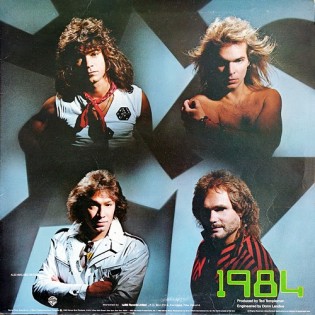

In July of 1984, the circus came to town. The Velcros opened the concert; they’re still bragging about opening for Van Halen thirty years later. Amid a spectacle of lights and stage mounts and stimuli, David Lee Roth told us we were the best audience he’d seen in the last 99 shows. Out on the floor, I had my first kiss with a girl who invited me back to her hotel after the show, the same hotel name-checked on the back jacket of Van Halen II.

Nine months later, Roth left the band. The party was over.

***

Decades passed. Other than a brief revival of Van Halen infatuation in the early ’90s (during a period of intense devotion to the electric guitar) the band mostly fell off my radar as my tastes veered toward ’50s and ’60s jazz, Frank Zappa, Funkadelic, Laura Nyro, soul, baroque classical, instrumental world music, an ongoing dose of’60s/’70s rock. As my listening habits changed, my six-string sensibility gravitated away from the technical playing that dominated the ’80s to the electric blues (Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan in particular). Even so, I slowly acquired the first six Van Halen CD’s—just in case.

Decades passed. Other than a brief revival of Van Halen infatuation in the early ’90s (during a period of intense devotion to the electric guitar) the band mostly fell off my radar as my tastes veered toward ’50s and ’60s jazz, Frank Zappa, Funkadelic, Laura Nyro, soul, baroque classical, instrumental world music, an ongoing dose of’60s/’70s rock. As my listening habits changed, my six-string sensibility gravitated away from the technical playing that dominated the ’80s to the electric blues (Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan in particular). Even so, I slowly acquired the first six Van Halen CD’s—just in case.

The separation ended in 2013, during an especially challenging time in my life. As if dipping my toes in the water, I put just a handful of tunes from each Roth album on my iPod.

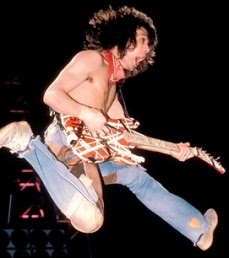

Soon I was hooked all over again. For months the band provided aural therapy as I crossed San Francisco sidewalks, the music mainlined into my ears loud and clear. With 25 years of electric guitar under my belt, I appreciated Eddie’s innovative sound(s) in a way I hadn’t before.

I’ve been a born again fan ever since. It feels like we never parted, as if we’ve been joined in a continuous line running from the moment I cracked the plastic on my “1984” cassette up to the present. Looking back from the vantage point of 2015, the final album with David Lee Roth represents a crossroads for this listener. Working from his home studio and freed of the shackles of hit-centric producer Ted Templeman, Eddie created an entire album’s worth of original material, a major achievement in itself and a big step up after the covers-heavy “Diver Down.”

I’ve been a born again fan ever since. It feels like we never parted, as if we’ve been joined in a continuous line running from the moment I cracked the plastic on my “1984” cassette up to the present. Looking back from the vantage point of 2015, the final album with David Lee Roth represents a crossroads for this listener. Working from his home studio and freed of the shackles of hit-centric producer Ted Templeman, Eddie created an entire album’s worth of original material, a major achievement in itself and a big step up after the covers-heavy “Diver Down.”

And yet, the synthesizer-based tunes on “1984” not only sound dated (in the way that ’80s production values sound dated), but they remind me of the sappy, formula pop songs the band did with Sammy Hagar which made me lose interest in Van Halen.

I love “Panama” and “Hot for Teacher.” They’re kinetic, well-crafted songs that have stood the test of time. But like “Stairway to Heaven” or “Layla,” I’ve heard them too many times to count.

What remains freshest in my ears are The Big Four: four guitar-oriented album tracks which connect me with the life force that put the mighty in The Mighty Van Halen.

Closing side 1 of “1984” in grand fashion are “Top Jimmy” and “Drop Dead Legs.” Before I knew who the real Top Jimmy was, I thought the song might be a veiled ode to the virtuosic Eddie, who makes his mark from the opening with ethereal harmonics counterpointed by a slashing riff, as a volume swell trills in the background. The verses have a swing that could only exist in the Roth era. The solo opens with a patented Eddie whale shriek and ends with a quivering tremolo dive that sounds like it’s falling down a mine shaft.

Recently accused of helping cause Ebola, “Drop Dead Legs” has a lumbering beast of a main riff (modeled on “Back in Black”) that is pure Van Halen strut. The MXR Phase 90 tone Eddie opens with is pristine, the drumming simple and powerful. The last minute-and-a half—tacked on after the rest of the song was already recorded—is a singular outro inspired by Allan Holdsworth. After vamping for a spell, Eddie breaks away from his typically disciplined pop-length solos with asmorgasbord of shapes and colors and sounds, a rare display of Van Halen’s free-form side.

The other two tunes on my active playlist are the closers on side 2, “Girl Gone Bad” and “House of Pain.” The former, which Eddie wrote in a hotel closet while Valerie Bertinelli was sleeping in the room, is an advanced composition that clocks in at 4:30. The wealth of ideas begins with Eddie tapping harmonics high on the neck while holding chords (with the same notes) at the low end as Alex taps insistently on the hi-hat, then the ride. The verses are short and to the point and transition—with Roth’s Tarzan yowls—into a fresh interlude at 2:16. The rest is gravy: following a soft landing from the solo into Eddie’s arpeggiated lines, the opening theme re-appears en route to another pass through the chorus. Alex brings down the curtain with a sweeping flourish that drops into a Rototom-and-kick drum stomp.

My favorite tune on “1984” is “House of Pain,” a song with distinctly Rothian tongue-in-cheek lyrics. The crushing main riff alone is worth the price of admission. Transitioning from the opening riff into the first verse, Eddie maintains the hard edge with a propulsive rhythm guitar line. The solo proper is merely a prelude to the outro solo at 1:42, introduced with a screeching pick slide capped by a taut snare hit. What follows is a heady demonstration of the musical telepathy a drummer and guitarist working in tandem for 15 years can generate. Over Alex’s driving beat Eddie conjures a wicked assortment of squeals, howls, dive bomber sounds, and serrated blues licks. He comes out of the squall into a boogie blues riff doubled by a vocal line, a final dance with Diamond Dave before Eddie, Alex, and Michael Anthony march one of posterity’s most kick-ass rock ‘n’ roll bands over and out for the last time.

A lot of the music I listened to in the ’80s seems like a guilty pleasure now, but Roth-era Van Halen still feels vibrant. And no one since has re-calibrated the sonic possibilities of rock guitar the way Eddie Van Halen did. As a player, I haven’t found a way to incorporate his space age techniques into my straight ahead blues style, but as a listener, I remain in awe.

Happy 60th, Eddie.

Check out Truth and Beauty for more from Dan Benbow.