Story by John Scanlan (Author of Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock’n’Roll)

Continued from Part 1.

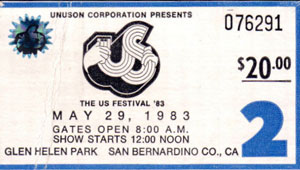

Roth’s return from the Amazon was just in time to prepare for a giant outdoor show Van Halen were co-headlining in San Bernardino County, California. The US festival, styling itself as a latter-day Woodstock, had been named “us” as in ‘we’—not US, or “United States.”

Roth’s return from the Amazon was just in time to prepare for a giant outdoor show Van Halen were co-headlining in San Bernardino County, California. The US festival, styling itself as a latter-day Woodstock, had been named “us” as in ‘we’—not US, or “United States.”

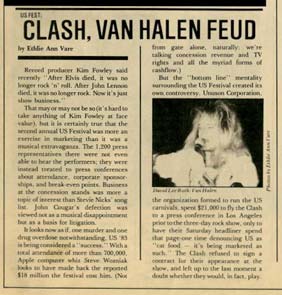

They were, though, only one of three headline acts appearing at the three-day festival—the others being David Bowie and The Clash, who had been riding high in the States on the heels of the previous year’s Top Ten Combat Rock album. In a series of press conferences to publicise the festival, where he declared himself “Jah Roth”, Dave bemoaned the absence of Culture Club from the bill, but spoke admiringly of all the money the promoters were pushing his way. Talk of the money, though, only served to alert The Clash to the fact that they – with their guaranteed $500,000 cheque – had been valued at just half the price of Van Halen.

With a heavy media operation talking up the neo-hippie “us generation” piffle of the organisers, led by Apple computer co-founder, Steve Wozniak, all of a sudden there seemed to be just a whiff of discord in the air. “You are going to be part of an event so big, so different it will begin a whole new chapter in the history of live music”, the US promo materials ran: “We will be joining together in a celebration that will mark the end of the ‘me’ decade and the beginning of the ‘us’ decade.” But as the pseudonymous Laura Canyon later reported in Kerrang!, what was going on was somewhat at odds with the ethos of “sharing” and “working together”.

“Yes, there were acrobats. There were hot-air balloons and computer displays in giant tents dotted around the grounds. But you’d be pushing it to call it a festival. For that matter you’d be pushing it to call it ‘us’, what with the acts divided from the fans and each other, the police and the punters totally split . . . and each of the three days divided by the genre of music, with tickets sold separately as opposed to as an overall event.”

“Yes, there were acrobats. There were hot-air balloons and computer displays in giant tents dotted around the grounds. But you’d be pushing it to call it a festival. For that matter you’d be pushing it to call it ‘us’, what with the acts divided from the fans and each other, the police and the punters totally split . . . and each of the three days divided by the genre of music, with tickets sold separately as opposed to as an overall event.”

Stuck in the “95-degree heat, dust and humidity” of the near-desert location, as the Los Angeles Times reported, agitated fans broke into sporadic fighting. “There was plenty of drug usage and scattered violence . . . and one death from an early morning fight in a parking lot.”

But of all the bands on the bill, it was The Clash who were torn – mad with rage, on the one hand, that they were being paid less than Van Halen, yet, on the other hand, acutely aware that now the word was out about who was being paid what, they could look greedy regardless. So, Clash spokesman Kosmo Vinyl leapt into action, intent on making sure all this money was seen as nothing to do with them. Bernie Rhodes, manager of the Clash, also told press gatherings that they were asking the organisers to give a proportion to good causes. “We’re trying to get Mr. Wozniak, who started this whole thing off in the name of money, to put some money back into California. With the figure of $18m being spent, we figure he could give 10% of that to some organization.”

But of all the bands on the bill, it was The Clash who were torn – mad with rage, on the one hand, that they were being paid less than Van Halen, yet, on the other hand, acutely aware that now the word was out about who was being paid what, they could look greedy regardless. So, Clash spokesman Kosmo Vinyl leapt into action, intent on making sure all this money was seen as nothing to do with them. Bernie Rhodes, manager of the Clash, also told press gatherings that they were asking the organisers to give a proportion to good causes. “We’re trying to get Mr. Wozniak, who started this whole thing off in the name of money, to put some money back into California. With the figure of $18m being spent, we figure he could give 10% of that to some organization.”

In the days and weeks leading up to Memorial Day weekend, Van Halen’s fee had initially been one million dollars, but as soon as David Bowie reputedly asked for a million-plus, the figure now due to Van Halen immediately rose to $1.5m without any effort on their part—simply due the guileless Wozniak agreeing to a clause in their contract that guaranteed they would be the top paid performer at the event. “We never asked for the money”, Eddie Van Halen said later of the $1.5m: “they offered it.”

Amidst all this, Kosmo Vinyl—“the loudmouth The Clash keep on their payroll to rile things up when their energies flag”, Record magazine’s John Mendelssohn noted in his dispatches from the event—was caught muttering disparagingly about Van Halen and their “hamburger music”. Roth, though, was a dab hand at the verbal volleyball himself, once declaring that life was best treated “as if it was the Charge of the Light Brigade – even if you are only going to brush your teeth.” So, he merely returned Kosmo’s ball with added swerve, damning The Clash with faint praise. “Look, I love The Clash,” Roth told the assembled press backstage. “I love Should I Stay Or Should I Go . . . mostly because I loved Mitch Ryder’s Little Latin Lupe Lu all those years ago. But, I fully understand The Clash’s position. They’re trying to effect some cultural change, and it’s tough – they’ve got a new drummer to break in, man. They’ve got their hands full—you know what I’m sayin’?”

Amidst all this, Kosmo Vinyl—“the loudmouth The Clash keep on their payroll to rile things up when their energies flag”, Record magazine’s John Mendelssohn noted in his dispatches from the event—was caught muttering disparagingly about Van Halen and their “hamburger music”. Roth, though, was a dab hand at the verbal volleyball himself, once declaring that life was best treated “as if it was the Charge of the Light Brigade – even if you are only going to brush your teeth.” So, he merely returned Kosmo’s ball with added swerve, damning The Clash with faint praise. “Look, I love The Clash,” Roth told the assembled press backstage. “I love Should I Stay Or Should I Go . . . mostly because I loved Mitch Ryder’s Little Latin Lupe Lu all those years ago. But, I fully understand The Clash’s position. They’re trying to effect some cultural change, and it’s tough – they’ve got a new drummer to break in, man. They’ve got their hands full—you know what I’m sayin’?”

After threatening to walk out on the eve of their show, The Clash relented. Bernie Rhodes told the assembled press that “the people out there want us to play. Besides, if we didn’t play, Van Halen would call us communists.”

After threatening to walk out on the eve of their show, The Clash relented. Bernie Rhodes told the assembled press that “the people out there want us to play. Besides, if we didn’t play, Van Halen would call us communists.”

The Clash’s protests about money not being used to support charitable causes and local bands were, in the words of biographer, Marcus Gray, “suspicious – given that they had specifically recruited a drummer for the gig, after being offered half a million dollars, and only began complaining after they discovered Van Halen were being paid more.” Guitarist Mick Jones even admitted later that the band “all knew that we were just doing it for the money.”

When the The Clash took to the stage with a slew of insults Strummer directed at the audience it was as if they hadn’t yet reconciled themselves to the fact that they were still there. “We’re here in the capital of the decadent U.S. of A,” he shouted. It was a performance that ended with scuffles onstage and recriminations off; between members of The Clash’s entourage and the festival organisers, and between Joe Strummer and Mick Jones of the Clash, who were now barely on speaking terms with each other. “Unfortunately”, John Mendelssohn wrote, “no one was hurt.” It was to be guitarist Mick Jones’s last performance with the band.

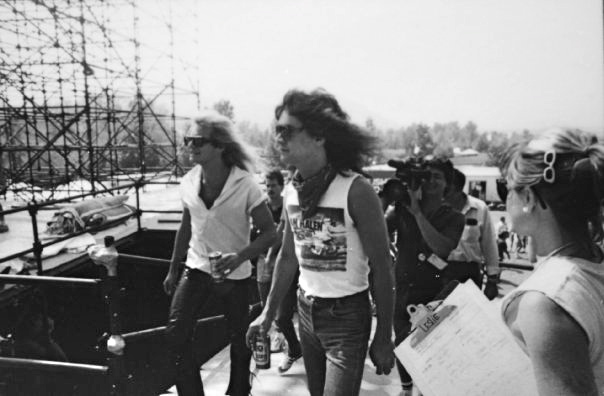

On the day of the gig, the Los Angeles Times reported that Van Halen’s half-acre backstage area—entered via a pathway signposted “No virgins, Journey fans or sheep allowed on trail”—had been set up for a huge party for 500 guests who helped themselves to “strawberries the size of baseballs,” and “barrels of iced-down beer scattered around the enclosure.”

Onstage, in between hearty slugs taken from a bottle that was passed between Mike Anthony, Roth and one of his two bodyguards (now was dressed as a waiter—appearing onstage between songs with a tray of Jack Daniels Whiskey), the singer addressed the audience: “I wanna take the time to say that this is real whiskey here. The only people who put iced tea in Jack Daniels bottles is The Clash, baby!!” San Bernardino County Sheriff, Floyd Tidwell, whose officers policed the event, afterwards accused Roth of inciting violence by purposefully stopping the band’s performance mid-song on a number of occasions to regale the audience with reports of their own mischief, and at one point yelling, “let’s get the cops.”

Onstage, in between hearty slugs taken from a bottle that was passed between Mike Anthony, Roth and one of his two bodyguards (now was dressed as a waiter—appearing onstage between songs with a tray of Jack Daniels Whiskey), the singer addressed the audience: “I wanna take the time to say that this is real whiskey here. The only people who put iced tea in Jack Daniels bottles is The Clash, baby!!” San Bernardino County Sheriff, Floyd Tidwell, whose officers policed the event, afterwards accused Roth of inciting violence by purposefully stopping the band’s performance mid-song on a number of occasions to regale the audience with reports of their own mischief, and at one point yelling, “let’s get the cops.”

“More people have been arrested today alone than the entire weekend last year,” Roth exclaimed to riotous applause near the beginning of the show. “You a bunch of rowdy motherfuckers!” In the following days, amidst the wreckage of the deserted site, a disgusted Sheriff Tidwell told the assembled press that “there are some people I’d be happy never to see back in this County again—Van Halen, for example.”

With sessions for the MCMLXXXIV/1984 album having begun at Eddie’s new studio the month before the Us Festival, in April, Roth and Ted Templeman, in particular, had to adjust to new recording conditions, and a new attitude to time and work. The first song to be cut at the studio was Jump, a song that Eddie had been trying to get the band to record for a couple of years. Eventually, he had to forge ahead on his own. “I put it down with a Linn drum machine, but when I played it for the rest of the guys in the band they said, ‘Look, Edward, you’re a guitar hero. Don’t stretch yourself too thin. Don’t start playing other instruments.’” When they finally caved in, the song was duly recut by the whole band in a single take.

With the instrumental track on a cassette tape, Roth left to work on the lyrics and vocal melody in his own peculiar fashion—which just happened to involve being driven around the Los Angeles canyons and along the Coast Highway by Larry Hostler, his roadie. “We get into the 1951 low-rider Mercury painted bright orange and red with a white pin-stripe down the middle, Larry drives and I sit in the back . . . and I write the songs. We play the tape over and over again on the stereo and about every hour-and-a-half I lean over and go, Say, Lar, what d’you think of this?”

With the instrumental track on a cassette tape, Roth left to work on the lyrics and vocal melody in his own peculiar fashion—which just happened to involve being driven around the Los Angeles canyons and along the Coast Highway by Larry Hostler, his roadie. “We get into the 1951 low-rider Mercury painted bright orange and red with a white pin-stripe down the middle, Larry drives and I sit in the back . . . and I write the songs. We play the tape over and over again on the stereo and about every hour-and-a-half I lean over and go, Say, Lar, what d’you think of this?”

Jump was, in its sentiments at least, squarely in keeping with the stress Roth placed on being in the moment. But, more than that, the song worked because the words and the sentiment actually match the feel of the music. The bridge section in particular, with Eddie playing a tastefully chosen guitar lick and Alex complementing him on cymbals, actually give the sense, like the title of the song itself, of becoming groundless; of being lifted up by a gust of air.

Backstage at the Us Festival, in late May ’83, David Lee Roth told MTV that the band had already been in and out of the studio. “We’ve got the singles down, and the rest of it is coming along quite well.” When asked about the release date and title, however, he admitted, “I haven’t the vaguest idea.” At that stage, the singles were Jump, Panama and Hot for Teacher. The album’s fourth single, I’ll Wait, existed in a state of limbo until a few weeks before the album was mastered in October ’83.

After the Memorial Day weekend shebang, there continued to be further interruptions to the MCMLXXXIV/1984 sessions. Roth split for a holiday in Mexico, and Eddie and his wife, Valerie Bertinelli, moved into a Malibu beach house they had rented for a couple of months. During days of experimentation—and much to the later horror of the owner of the house, the schmaltzy composer, Marvin Hamlisch—Eddie all but destroyed a white grand piano that came as part of the rental deal. Taking a saw to it, and stuffing its insides with a variety of kitchen implements, he recorded hours of John Cage style “piano abuse”. Although none of this has ever really seen the light of day – aside from a one-minute snatch on 1996’s Balance album – Eddie enjoyed pulling out the tapes and playing them to bemused journalists who interviewed him during the 1984 tour, if only to show how “fucked-up” he really was when given free reign.

But whatever was going on there in Malibu, and back at the studio in Coldwater Canyon, it began to test Roth’s patience, especially when it emerged that Eddie and Donn Landee had seemingly put the album on hold to record incidental music for a TV movie that Eddie’s wife was starring in. At times, Roth later wrote, it descended into “the type of ludicrous behaviour where I’m sitting with the producer in one studio in Hollywood, while Ed and the engineer are in another studio.” Eddie and Donn Landee would be “working all night, not getting up during the day,” Roth said, and “threatening to burn the master tapes” if he and Templeman didn’t quit trying to obtain some of them to work on at another location. They found themselves hanging around outside 5150 “for four and five days in a row, waiting for Ed to pick up the phone in his bedroom, knowing he was in there but wouldn’t pick up.”

That was the beauty of the new studio set-up for Eddie: it enabled him, at a stroke, to side-line the disciplinarian Templeman – a self-declared proponent of “Nazi” working methods, and triumphant survivor of studio battles with such hard-headed and “difficult” artists as Van Morrison and Captain Beefheart. “Ted sure didn’t like working at 5150,” Eddie said. “He thought I’d just throw him out if I didn’t want to hear what he had to say.”

There is, of course, nary a hint of such discord on the album itself.