The human voice is our most widely used instrument, and one we don’t often care for properly. From public speaking to fronting a band, voices take abuse on a daily basis, and with neglect, the damage may become irreparable.

Voice teacher Peter Strobl knows this, not only as an instructor, but also as a student who once damaged his voice under improper tutelage. Strobl was fortunate to be able to rebuild what he had lost, and since then, he has dedicated himself to teaching others the proper techniques to use and protect their voices.

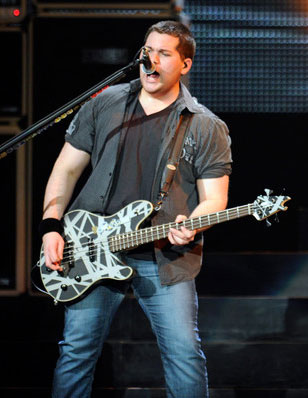

His journey to becoming an esteemed voice teacher is a fascinating one, filled with art, culture, European influences and a lot of rock and roll. Additionally, Strobl is a musician, luthier and producer, and his talents have taken him around the world. He’s also the teacher behind those spot-on background vocals you hear on Van Halen’s A Different Kind Of Truth and onstage.

What are some of the techniques and methods you use and how do they vary from, let’s say, Wolfgang Van Halen, who is a rock musician, versus an opera singer, versus someone who solos in the church choir?

What are some of the techniques and methods you use and how do they vary from, let’s say, Wolfgang Van Halen, who is a rock musician, versus an opera singer, versus someone who solos in the church choir?

Great question. I first started working with Wolfie previous to the 2007 tour. I initially started working with Ed and Wolfie on their background vocals. Wolfie was 16 or 17, a young guy, a blank slate. Going back into teaching the mechanics of singing, we started at the very beginning with him, like, “Let’s make a sound.” Fortunately, he’s a really, really hard worker. We worked as hard as he could physically pull off in an hour-long session and built and built that voice. I’ve got to say, it’s like a case study. It really worked. Nobody would question the fact that he was lucky to be in the right place at the right time. But when those doors open, you better bring the good stuff, because if you walk in empty-handed, there’s a door out just like there’s a door in. You can be associated with whoever you’re associated with, but if you don’t have the goods, a guy like Ed is not going to have somebody onstage that isn’t cutting it. That isn’t going to happen. Regardless of what anyone thinks, it’s just not going to happen.

By comparison, a soloist with the church choir has limitations in that they’ve built a host of bad habits that aren’t conducive to disciplined singing, because they’re physically not helping themselves every day. It’s like a weekend warrior who goes to Venice Beach, plays basketball with the guys, gets the shit knocked out of him, and puts himself together again so that he can play next Saturday. He nurses whatever he broke that day and goes back and takes it again. A guy like that has no business doing warm-up drills with the Los Angeles Lakers.

An opera singer has a cultured pedagogy and well-defined approach to how they do things. At my Mozartaeum workshops, I worked with classical singers in the opera program who also wanted to sing pop songs. I had a soprano singing “Wind Beneath My Wings,” and it’s so difficult not to fall into that caricature of Pavarotti singing U2 songs. It just doesn’t work very well, because with pop songs you have to pay attention to what you’re singing, not how you’re singing it. You have to unlearn and take your technique off the pedestal and think more about communicating. Singing is like talking, but with art involved. You’re artistically communicating an idea. If somebody can’t accept the song because they can’t connect with your way of singing, or the self-absorbed way of hooking into all those years of voice lessons you took, then you’re not accomplishing anything. Ultimately, you have to connect with your audience, and if your audience is saying, “My, what masterful breath control,” or “I love the way she approached the fricative consonant on the sixth degree of the scale,” then you haven’t accomplished what you set out to do. The only thing they should walk away with is, “God, I love that song! Oh, that was so beautiful.” That’s when you know a singer has really done their job.

Studio singers who sing background are a whole other deal. More often than not, background singers are technically better than the people they’re singing behind, because they have to sing in tune and they have to sing on time. They’re expected to do it right the first time, where a lead singer has leeway because you’re talking about personality.

In the case of a total beginner, a clean slate, I always start with mechanics. And my first pitch goes something like: “This is going to be really intensive, it’s going to take a long time, a lot of hard work, and there is no shortcut. You’re not going to be singing a high C at 3:30 this afternoon or on Wednesday or two weeks down the road, if you’re not able to do that right now. But I can tell you that three months down the road, if you do what we decide you should do, possibly you’re going to be a lot closer. If you don’t cheat yourself and you work hard as hell every day, then six months down the road you’re going to have something worth talking about that you couldn’t have had any other way.” I mean, I can manipulate you into thinking you can hit a high note right now, but that’s not going to turn you into a singer. So when you’re talking about the guy at the piano doing repetitive vocal drills, I did a lot of that with Wolfgang, hour after hour after hour, because the physical repetition of doing that builds the habit so you don’t have to think about it. When you’re onstage and you’re singing in front of 20,000 people, you can’t be thinking about, Do I have my mouth open enough, did I take in enough air, is my uvula arching correctly, did I drop my jaw, am I resonating in my sinuses? That’s the furthest thing from your mind. You’re thinking about singing the lyrics to your songs so that people drive home singing the hooks to these songs and going, “Damn, man, they rocked!” You can’t be mentally involved with the technique. You’ve got to do that early. It’s like the great [UCLA basketball coach] John Wooden. He didn’t do a lot of coaching during games. He did his coaching in practice, where he busted those guys’ cookies and made them the fastest, quickest-thinking athletes they could possibly be, so that when they hit the court, he could just sit back and enjoy the game. He knew that his guys knew what to do because they had worked their asses off.

Let’s back up. You coached father and son?

I worked with Ed for a while. He would sit on the piano bench next to me and we’d work on relaxing, breathing properly, chilling out and letting the words come out, rather than looking up and trying to scream them out. He’s written so much of that stuff, it’s his music, so it shouldn’t be difficult for him to do, but when you’re trying to step out of yourself, it can be daunting. When Ed is standing on a stage and playing with reckless abandon and smiling, he’s such a pleasure to watch work that I don’t even want to call it work. The whole singing thing should come easy to somebody like that, so if you apply a few techniques to make it even easier, then your audience is going to have a treat. If the singer is laboring, the audience picks it up and they’re laboring with you. No matter what is happening on the stage, most of the audience relates most empathetically with the singer. If he’s breathing in uncomfortable places, the audience will breath along with him and they’ll be just as uncomfortable. They won’t have any idea why, but they won’t enjoy the experience.

For example, a guitar soloist doesn’t have to breathe. They just play as long and fast as they can, and that kind of stuff is harder to listen to than a guitar player who plays phrases that he breathes, because the audiences gets to breathe with those phrases and it makes it a more pleasant experience. With singers, it’s absolutely critical that they breathe in logical places so that the audience breathes with them, and nobody passes out while they’re trying to finish a difficult line.

With Wolfgang, knowing that a singer is going to be playing an instrument while they’re singing, I think it’s very helpful to put the instrument in that person’s hand and have them play the vocal exercises. Pretty early on I’d say, “Go grab a bass and learn the sequences and play along while you’re singing,” because it brings rhythmic integrity into the picture. It ties in what you’re doing with both of your hands at the same time that you’re using your face and your breathing muscles. You can build vocally all you want, but the minute you put an instrument in your hands, all bets are off because now you’re doing two things at once.

This is something I discovered years ago. I had moved into a new apartment and my piano was completely out of tune. I had students coming in that week and I couldn’t use the piano, so I used a bass and played the vocal exercises. Think of what this will do for intonation when you learn to relate to the dominant note in any instrument group, which is the bottom end, the bass. If you’re not relating to that, you’re just floating around and hoping you get the pitch, but if you relate to that, it makes you a much more accurate singer. Sure, you can bend notes, there are reasons to drift occasionally. But knowing that you’re drifting is better than drifting because you don’t know any better. So for guitar players and bass players, I think it’s really important to play the exercises as you do them, because then, when you’re backstage and warming up, you don’t need to have Schleply Shlemazel at 500 bucks an hour from Studio City to warm you up. You can sit in the dressing room, put headphones on, plug in your guitar and warm up. By the same token, I teach guitar and bass as well, and when students want to learn to solo, I don’t let them throw their fingers around. I make them sing every note they’re playing, because that makes them play it more as if they were singing it. All of a sudden, some of them go, “I didn’t even know I could sing.” It ties it all together.

You trained Wolfgang for the road. For an artist who sings in the studio, onstage and on tour, do you use the same techniques for each medium or are they different? On the road, the temperature is controlled for you, you change venues every night, you live in hotels and on a bus, you’re in and out of airports and airplanes, sleep is disrupted and so forth.

Getting ready for the tour was a pretty daunting task because it’s not like you’re ramping up by playing clubs for ten years. All of a sudden, bam, there’s 20,000 people who paid a lot of money — sing! It’s a really big deal. So it was the fast track. The first thing we worked on instantly was posture, standing in a way that somebody isn’t going to be able to knock you over, standing in a way that, when you’ve got your instrument on, you’re able to physically do the things you need to do to make those sounds project into the microphone. Immediately, we had to shift even the position of the microphone because they were singing with the microphone pointed down. They were singing with their chins reaching up into the microphone. I don’t know what the thought process was. I’ve seen other people do that, thinking that if you look up, you can hit high notes, which is erroneous. So we were immediately figuring out how to work within the environment that the tour was going to entail: standing onstage with a microphone in your face, as opposed to just building a voice. We had to do two things at once.

Then it was building endurance, because singing “Somebody get me a doctor” forty times in three minutes takes a lot out of you, even if you were just standing there. But you’ve got a bass on and you’ve got to walk around and connect and everything else. The first thing we approached was breathing exercises, phonating, creating a sound. Then I looked at what he was being asked to sing, and how do you start these consonants at the beginning of these words and start them in a way that’s going to efficiently make that happen? What’s the difference between saying the word and singing the word up really high where he’s got to do it? How do you approach that and come up with exercises? “Running With The Devil” starts with the American letter R, which is a killer because it has pitch, “er,” so how do you go “er-unning with the devil” without ramping that up? As a background singer, you have to be there first. You have to make that R on the same pitch as the “unning.” So it was coming up with exercises where you do five or ten R’s in a row repetitively so that your tongue, and the muscles in the back of your throat, and your brain all know what to do without you having to remember, “Don’t scoop every time you open your mouth, every time you step up to the microphone.” That’s where repetition comes into it. And there is no shortcut.

Scoop?

Scoop is going from one pitch to the next — “running,” even when I say it, the “er” is down here and the “unning” is up there, so when you say it on a pitch, the R has to be thought on that top pitch because your diaphragm and your breath are not engaging fast enough. You’re not starting singing while you’re doing the R. You’re starting singing after you’ve done the R, which is too late. There are a ton of consonants like that — M, D, B — so you have to do exercises that highlight those consonants and the right vowel of what it is you’re going to be singing, specifically make those repetitive, and hammer them home so that you don’t have to think about them anymore. When they come up in a song, your technique has to be evolved to the point that it just happens, rather than, “Oh, I’d better think about this.” That’s just too late.

What type of schedule does the student undertake in order to do this?

In Wolfgang’s case, I worked in their environment. I went to them and worked with him in his comfort zone. We worked three and sometimes four or five days a week in a row, whenever they were rehearsing. When they were rehearsing for the album, they rehearsed like crazy. When they were doing the writing sessions and rehearsing, I would go in on rehearsal days, two hours before the rehearsal, and work, work, work, and then he’d be tuned up and ready to rehearse. When they moved to Henson, I would still meet them at 5150 and work there before. He’d go from there to the recording studio. He was really intense. If everybody, everywhere, worked that hard, they’d all be good at what they do. Wolf is no joke. There’s a reason why he’s doing as well as he does — because he works really hard. It was really intense before recording. We were working three or four days a week. When you train for the studio, you train for specific situations. What are the songs you’re singing, what are the words you’re singing in those songs, and then you get really specific. Getting ready to go on tour, you can be a little bit more general about it because you want to build stamina, you want to build good habits, and you also want to build the ability to spit out the best you’ve got and be able to do it night after night.

In the studio, if you get it that one time and you really kill it and it’s there forever, then you’ve got to come up with a way to do it every time. Everybody goes, “That was amazing,” which is a blessing and a curse because you might only have one of those in you and then you end up chasing that forever. When you get ready to go out on tour with that, you have to do that over and over again. Years ago, I was musical director for Gary Puckett for six and a half or seven years. Gary is an amazing singer, he made some incredible records, and as a vocalist he was at the top of his game when he made those records. But can you imagine having a zillion-selling record and having to sing that hit song over and over and over again and having to sing it the way you recorded it? Unless you like to wear the same T-shirt and shorts every day, you want to do things a little bit differently and be creative, and it’s difficult to do if your song is a classic iconic performance. You have to do it exactly the same. It can get to be boring, but you can’t let it.

How does the artist continue his work?

It really depends on the level of the artist. I like to think that people who work with me, in addition to knowing what they’re supposed to be doing, end up with a confidence level that is conducive to being an ass kicker as opposed to being an ass kickee. I think the world is divided into those two kinds of people. You reach a point where you might say, “I need to see Pete about this,” or “That work I did with Pete gives me the ability to figure this out myself.” It could work either way. Some people are more comfortable with seeing my face, but I’m just as happy with someone who has learned to be an ass kicker and faces things head on, although I’m always happy to get together and see where the problems are, because there are always ways to improve — always.

How does the artist practice on the road? Regardless of the stereotypes, it is a grueling lifestyle, much more so than most people realize.

First of all, I don’t think that the average person has any idea what touring takes out of you and what these people do for a living. They don’t have any idea the level of the physical demands that it puts on you. Eating strange food, sleeping in a strange bed, traveling all the time — it adds up to potential disaster looking for a place to happen. For most of the people I work with, I record the exercises and they walk away with a CD or a USB flash drive. They load it into their iPod and they’ve got a routine of 15 or 20 minutes, maybe a half hour, that they can do as many times a day as they want, because there’s nothing there that’s going to hurt them. It’s all geared toward building. If there are specific lyric issues, we’ll address those and put a routine together. In Wolfie’s case, he’s able to play whatever he needs to, so I would hope that he takes a little bit of time every day and works on whatever weaknesses might come up. The last time we walked out of the rehearsal studio he was in great shape, and at his age I would expect him to just get better. The tenor voice, which is the high male voice, doesn’t really mature until you’re close to 40. That’s when it starts hitting on all eight cylinders, so if you’re not killing yourself, you’re going to keep getting better as long as you’re doing things properly and in a way that is conducive to building the voice rather than tearing it down.