Eight years ago today, the legendary Edward Van Halen appeared at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington D.C., headlining an event that was part of the national “What It Means to Be American” program.

The three-year initiative is aimed at engaging leading public thinkers and Americans in all walks of life to explore how the nation has become what it is today.

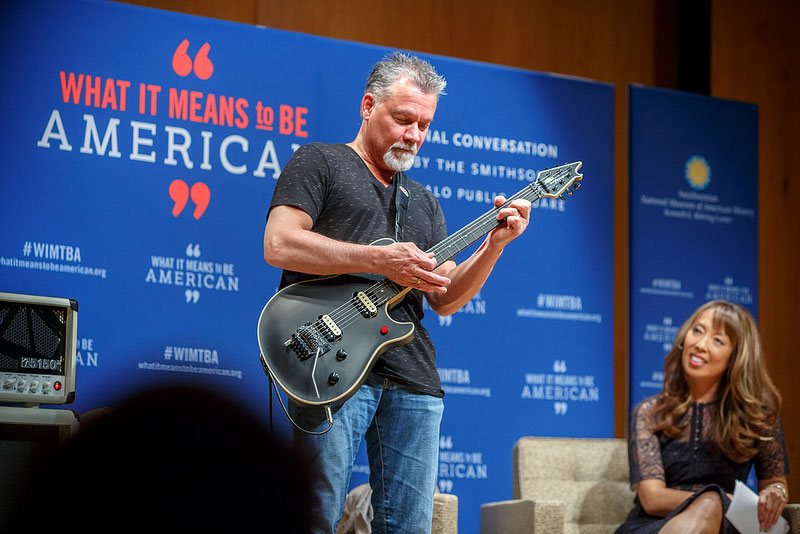

As part of the event, Van Halen and EVH Gear donated three new pieces of gear to the Smithsonian, including a prototype replica of the original black and white guitar from 1978, a replica of the current EVH Wolfgang Stealth and a half stack EVH 5150III. These items join the previously donated Frankenstein replica from a few years ago.

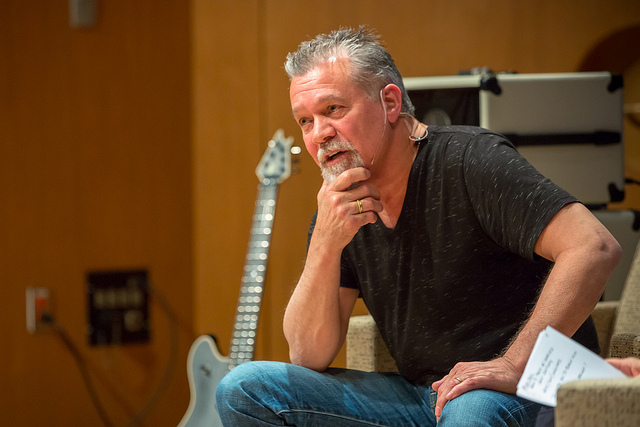

The famed guitarist also took part in an hour-long discussion with former CNN entertainment reporter Denise Quan that centered around the question “Is Rock ‘n’ Roll All About Reinvention?” A Dutch immigrant and naturalized U.S. citizen, Van Halen delighted the audience with recollections of his musical journey.

Watch the discussion above.

From WhatItMeansToBeAmerican.org:

Necessity Is the Source of Eddie Van Halen’s Inventions

The path to rock superstardom involves immigration, experimentation, and the occasional electrocution

By Sarah Rothbard

Feb 13, 2015

Rock legend Eddie Van Halen didn’t set out to change the way the guitar was played. But, as he explained to a standing-room-only crowd at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, music shaped his life—and his life shaped his music—in unexpected ways from his very first performances.

Van Halen’s father Dutch father was a classical musician who “traveled the world making music,” said Van Halen. He met Van Halen’s Indonesian mother while performing in her home country just after World War II. They got married and moved to Holland, where “life became a little rough.” Van Halen’s mother was a second-class citizen; she was stuck at home with “two rugrats” (Eddie and his brother, Alex) while her husband was away gigging for weeks at a time. So they decided to pack up the family and move to California—to “Beverly” (“it wasn’t Beverly Hills then”), said Van Halen.

En route to America by boat, Van Halen’s father performed with the on-board band during the nine-day journey. After their father suggested that his sons play during intermission, Eddie and Alex learned performance came with perks: The next night, they were eating dinner at the captain’s table.

In Southern California, Van Halen’s mother worked as a maid, and his father pursued music while working as a janitor. The family lived in one room in a house they shared with two other families. In a new country, speaking a new language, the one constant thread was music. “We always liked things loud,” said Van Halen. Nonetheless, he and his brother spent years playing classical piano—despite the fact that Eddie never learned how to read music.

Once the Van Halen brothers discovered rock ’n’ roll, they quit piano lessons. Eddie got a drum set, which his brother coveted.

“I never wanted to play guitar,” he said. But his brother was good at the drums, so Eddie gave into his brother’s wishes: “I said, ‘Go ahead, take my drums. I’ll play your damn guitar.’”

Music journalist Denise Quan, the evening’s moderator, then asked Van Halen to fast forward to 1978. That year, his band’s self-titled debut album hit stores—and turned the music industry on its head. Van Halen was making sounds “that no one had heard before,” said Quan.

In between taking up guitar and becoming a star, there were “a lot of years of experimentation,” said Van Halen—taking apart guitars, opening up amplifiers, and getting electrocuted. Some of that was driven by necessity. But a lot of it was just his nature. “I’m always pushing things past where [they’re] supposed to be,” he said. “When Spinal Tap was going to 11, I was going to 15.”

Van Halen knew the sound he wanted to achieve, but he couldn’t find a guitar that could make it. So he got different parts from different guitar-makers, including Gibson and Fender, screwed and soldered and melted them together, and built the instrument he wanted. (He has a graveyard of vintage guitars he destroyed for their choice pieces.)

Even the instrument’s paint job was unplanned: Van Halen painted the guitar black, but “it looked kind of boring,” he said. There was tape lying around, so he taped up the guitar, spray-painted it white, then removed the tape—and a new kind of guitar graphic design was born.

“Crossing a Gibson with a Fender was necessity,” said Van Halen. The paint job was not.

He customized his amplifier with the same combination of trial and error, tinkering and luck. He purchased a Marshall amp (the brand that “Eric Clapton and gods” used), not realizing it came from England and was 220 volts. He plugged it in—and heard nothing. But after warming the amp up to half voltage, Van Halen managed to get an “incredible” sound from it. The only problem: The sound was so quiet that only the guitarist and his dog could hear the music. Van Halen’s solution was to buy what was essentially a light dimmer at a local electronics store that allowed him to control the volume.

Van Halen’s innovation isn’t limited to his equipment. Quan noted that he pioneered the art of playing with both his right and left hands on the guitar’s frets. Grabbing a guitar, Van Halen talked about finding inspiration at a Led Zeppelin concert at the Forum in Inglewood, California. After seeing Jimmy Page play a lick with one hand on the guitar and the other raised up in the air, Van Halen decided to try placing his second hand on the frets as well. He played a few of the melodies that resulted to loud hoots from the audience.

The main reason he squeezed so many techniques out of the guitar was also “out of necessity,” said Van Halen. He couldn’t afford a wah-wah pedal, a fuzzbox, or other gear that created the processed sounds he sought. He had to rely on his fingers alone.

What advice, asked Quan, did your father give you that you wanted to pass on to your son, who is also a musician?

“You can learn from everybody,” said Van Halen—what to do and what not to do. Especially the latter. “If you make a mistake, do it twice, and smile,” he explained. That way, people will think you mean it. He shared a Dutch phrase of his father’s that translates into, “Just keep pedaling.”

Do you feel as though you’re living the American dream, asked Quan.

We came here with approximately $50 and a piano, and we didn’t speak the language, he said. Now look where we are. “If that’s not the American dream, what is?” he said.

In the question-and-answer session, a young audience member asked Van Halen to describe his first day of school in America.

“It was absolutely frightening!” said Van Halen. The school he and his brother attended was segregated. As non-English speakers, they were considered a minority. The white kids bullied them—tearing up their homework—and so their first friends were the black kids who stuck up for them.

If you were an unknown today, asked another audience member, how would you get your start in a very different music business?

Van Halen told him that things weren’t that different today. Then, as now, rock ’n’ roll was not nearly as popular as other genres. (Disco and funk reigned then, much like pop and hip hop today.) “For a good seven years, we knocked on everybody’s door” because nobody knew who Van Halen was, he explained. They made demo tapes. They played backyard parties. They photocopied their own flyers.

“We just humped it and humped it until people came,” he said. “I don’t see how that wouldn’t work today. Whatever music is out there, there’s always room for more.”

Editor: Jia-Rui Cook.

Photos by Abram Eric Landes.