.

Continued from Part 1, Part 2 & Part 3

Los Angeles also provides Roth’s canvas for “Top Jimmy”, but this time the picture he painted was more grounded in his day-to-day life. Easily the oddest cut on the album, it features Eddie sounding as if he is playing a guitar strung with elastic bands—partly the result of the fact that he is often slapping the strings. It is one of several tunes on the album – “House of Pain” and “Girl Gone Bad” being the others – that on closer listening develop a kind of swaying, disorientated, quality.

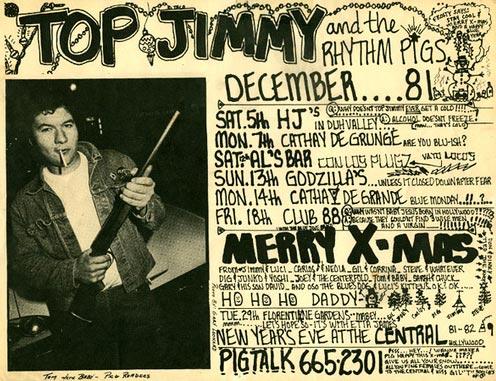

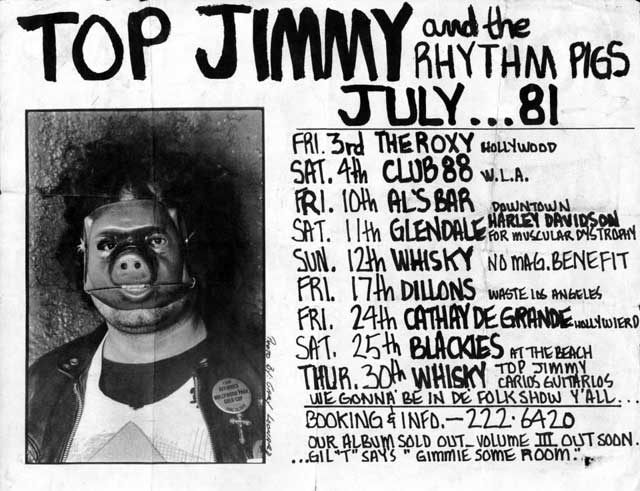

The “Top Jimmy” of the song was one James Koneck, leader of Top Jimmy and the Rhythm Pigs, whose nickname derived from his day job working a Top Taco stand outside of the A&M Records lot in Hollywood. He and Roth became friendly sometime around late 1980, when Dave became the “anonymous financial benefactor” of an after-hours club known as the Zero-Zero, which was then masquerading as an art gallery because it didn’t have a liquor license. “I met David when I was bartending at the old Zero-Zero club,” Jimmy recounted in a 1984 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Back when it was on Cahuenga—maybe three years ago. We got real drunk and sang a bunch of old blues together.” The Rhythm Pigs would play “60-some Monday nights at the Cathay de Grande,” the sweaty basement of a Vietnamese restaurant in North Hollywood where the events of Top Jimmy took place. “Tom Waits came in and sang Heart Attack and Vine one night. Dave used to get up and sing blues. Ray Manzarek, Albert Collins, Bonnie Bramlett, Percy Mayfield, the Blasters, X and—before she was in Lone Justice—Maria McKee, all came down and jammed with us.”

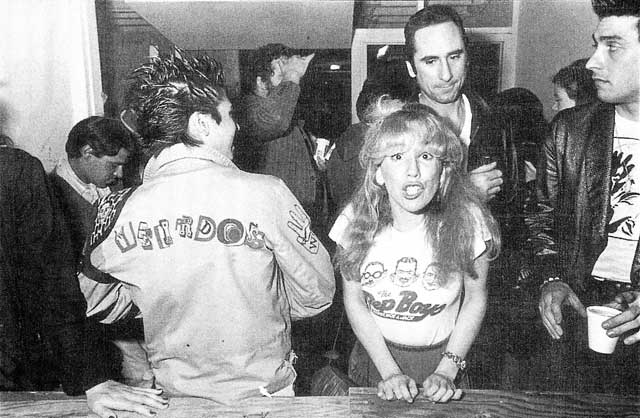

The Zero-Zero’s regulars included most of the members of LA’s exploding punk and alternative scene, as well as notorious party animals like the soon-to-be-dead John Belushi. Club founder John Pochna recalled that “David showed up at the Zero one night very early on and just loved it. He showed up the first time in a limo, and he had these two chicks with him and Eddie Anderson, his personal security guy. The chicks thought they were going to some fancy place … one of those classy, high-end rock places that Rod Stewart would hang out at. They completely freaked out when they saw the look of the place and this raw, totally fucked-up downscale crowd. The chicks were so bummed that David just sent them back out into the limo and then he’d continue to hang out and pick up other chicks … and then he’d send those chicks back and so it would go on and on until the limo was eventually stuffed to the roof with them.”

Brendan Mullen, the recently deceased owner of LA’s first punk club, The Masque—and also a partner in the Zero-Zero—remembers it as “the place on a cool summer’s eve to have sex on the hoods of cars with a joint and a fifth of Jack Daniels in one hand and a line of dope on the back of the other.” It was in the Zero that Roth would hold court in the back room, as beer and pills were swapped in the ramshackle bar area, where Top Jimmy was often to be found dispensing drinks.

As it happens, Top Jimmy’s title and lyrics were added very late in the making of the album, around September 1983. Until then this was just an instrumental titled Ripley, after Steve Ripley—the designer of the unique stereo guitar that Eddie played on the tune. Ripley himself had played with Leon Russell and Bob Dylan (and now leads the multi-platinum country act, The Tractors), and he and Eddie “just became best of friends,” he recalled in 1994. “He was a big supporter of my little company. I don’t how many guitars Edward bought—probably just masses of them.”

Once Roth got hold of the tune, though, it would end up being the tale of a night in 1981 at the Cathay De Grande, when Top Jimmy—as if in some great cosmic realignment—finally found himself amongst the stars: “Jimmy on the television / Famous people on there with him / Jimmy on the news at five …”

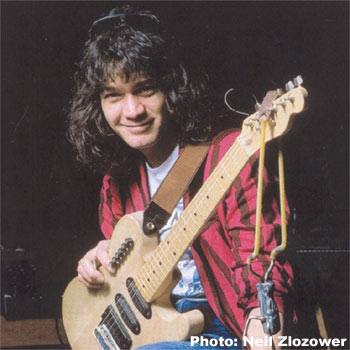

The opening 20-30 seconds of “Girl Gone Bad” feature one of Eddie’s most memorable musical phrases, when he taps out a series of breezy Miles Davis-ish syncopated notes on the neck of his guitar. “Sometimes the shit just hits you in the middle of the night,” he told Jas Obrecht of Guitar Player magazine. “We were in South America on tour, and I didn’t want to wake up my wife, so I hopped into a closet and hummed the guitar lick into a little tape recorder. You’ve got to force yourself to get out of bed and go, ‘Hey, this might be something someday’.”

The way the tune begins – with that kind of cool horn-like sound – probably has a lot to do with Eddie scat-singing those notes into a tape machine, dum-dum-dum-de-da-dum, de-da-da-dum-dum-dum. This figure, which recurs later in the song slightly altered, has a sense of the anticipated beat common to jazz.

The way the tune begins – with that kind of cool horn-like sound – probably has a lot to do with Eddie scat-singing those notes into a tape machine, dum-dum-dum-de-da-dum, de-da-da-dum-dum-dum. This figure, which recurs later in the song slightly altered, has a sense of the anticipated beat common to jazz.

“Girl Gone Bad” presents a slightly different Eddie than the world was accustomed to. Huge, uncharacteristic chords swell, suggesting nothing so much as heat—with each string bristling as he strokes downwards, almost in slow motion. To listen on is to hear a piece that carries us through space with so much going on that the only comparison—to these ears—is possibly with those bebop combos of twenty and thirty years before: Eddie, starting like Miles Davis is then transformed by the throbbing undertow of Mike’s bass and the way Alex’s kick drum really pushes the band along into some buttery John Coltrane flourishes from the guitar, and then back again to the restrained and cool horn sound of the song’s opening bars. It may be his greatest four-and-a-half-minutes of guitar artistry he released.

MCMLXXXIV/1984 ends, though, with the heavy sway of “House of Pain”, and with Alex beating the life out of some big cymbals. This, in itself, almost induces the bends as it threatens to become submerged in a muddy cacophony. A song with this very title and with a partially similar riff was recorded by the band back in 1976 when they cut demos with Gene Simmons of Kiss. But, really, what we have here is a very different song. On that demo, Eddie and Alex’s parts – aside from the main riff of the verse – were rather more one-dimensional than this “House of Pain”.

The revamped song also benefits greatly from a new opening—Alex comes in deceptively off-beat, under Eddie’s bendy, heavy chord opening, as if landing on the ground mid-earthquake, before the song lands on the old 1976 riff. But these thick, fat, guitar parts are not to be found on the earlier tune. As with “Drop Dead Legs”, Eddie achieves an almost sax-like feel and swing as we hear a band that is much more accomplished than it was in 1976. Roth’s lyric, too—aside from the title—is entirely different, much better, and sung to a new tune. And so ends the record, with a nod to the band’s early days.

Is that all there is? One thing that listeners new to the album today might note is how short the album—at just over 30 minutes—actually is. In 1983, the CD, with its 70-minute-plus capacity had just been launched. So, it was still common to think in terms of the vinyl album and its inherent limitations.

Speaking to Steve Rosen in late summer, 1983, Eddie said that they had “all the tracks finished for thirteen tunes but we can’t use them all. The songs are four to five minutes long and we don’t like putting more than thirty-five or forty minutes on a record because you lose that crispness. It starts sounding like a greatest hit package from the ’50s. You lose fidelity.”

Although rumours have circulated of a version of Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour”, a rendering of an old sea shanty titled “Blow the Man Down” (true to the spirit of Roth-era Van Halen), and other titles that were trailed by band members in the press—”Eat Thy Neighbour”, “Anytime, Anyplace”—it remains a mystery whether or not anything lies in the vaults. One thing that is true, however, is that Van Halen are perhaps unique amongst acts of their stature in never having expanded editions of albums, box sets and the like. Even in the old days, there was not a single 7” B-side that wasn’t already on the albums. In other words, they have always tried to keep strict control of what got out. Indeed, given Van Halen’s legendary fast-n-dirty recording methods—which were the norm prior to MCMLXXXIV/1984—it is perhaps likely that there are no significant leftovers: they went into the studio, cut their tracks in a matter of days, and left.

Nonetheless, Van Halen have always seemed curiously unmoved by their own legacy. A point underlined by the failure of any current band member to show up to be inducted into the Rock’n’roll Hall of Fame in 2007, and their unwillingness to rake over the past. Such gestures speak of a single-minded determination to opt for a kind of seventies style Zeppelin-style aloofness that sits uneasily with the expectations of an all-revealing internet age. There is perhaps something to be admired in this desire not to simply give the fans what they keep asking for—but it is a stance that perhaps also diminishes the work they have left behind which, at times, just seems to have been abandoned.

The sense of time and distance that had elapsed in the Van Halen camp by late 1984 was evident in small details—some of them obscure and little known. There was, for instance, the promo video for Miloš Forman’s 1984 film Amadeus, which consisted of a compilation of pop music video clips, all set to the music of Mozart and inter-cut with scenes of actor Tom Hulce as Mozart—all in an attempt to try and take the film to the new MTV audience. Significantly, David Lee Roth appears in the only specially-filmed segments, at the beginning and the end, as an absurd orchestra conductor dressed in a ludicrous—but supremely Rothian—cheetah-patterned suit and bowtie. Tumbling onstage like one of the Three Stooges, Dave brushes himself down and gathers his composure before rapping the conductor’s baton against a music stand to say, “alright gentlemen, I have to get this suit back by five, so let’s get it right the first time.”

The sense of time and distance that had elapsed in the Van Halen camp by late 1984 was evident in small details—some of them obscure and little known. There was, for instance, the promo video for Miloš Forman’s 1984 film Amadeus, which consisted of a compilation of pop music video clips, all set to the music of Mozart and inter-cut with scenes of actor Tom Hulce as Mozart—all in an attempt to try and take the film to the new MTV audience. Significantly, David Lee Roth appears in the only specially-filmed segments, at the beginning and the end, as an absurd orchestra conductor dressed in a ludicrous—but supremely Rothian—cheetah-patterned suit and bowtie. Tumbling onstage like one of the Three Stooges, Dave brushes himself down and gathers his composure before rapping the conductor’s baton against a music stand to say, “alright gentlemen, I have to get this suit back by five, so let’s get it right the first time.”

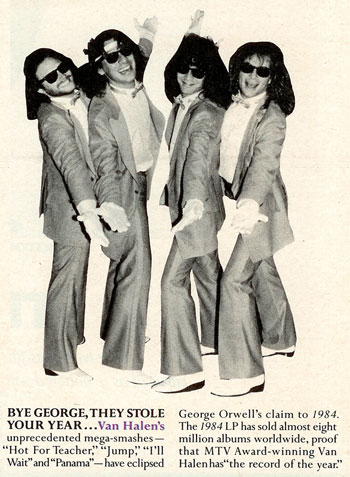

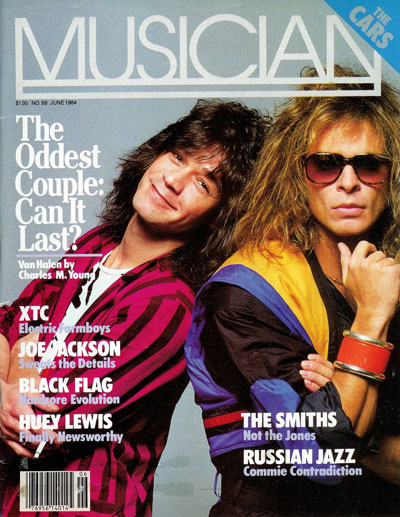

At the root of it all is David Lee Roth and Eddie Van Halen’s experience of making their last album of the ’80’s together, MCMLXXXIV/1984, and the perhaps uncomfortable realisation that, due to some cosmic accident, they will forever belong together, regardless of how they get along. “You can wonder what Roth and Eddie Van Halen are doing in the same band,” Charles Young of Musician wrote in 1984. “It’s hard to imagine two guys with less in common psychologically, yet together they seem to make a complete personality. Extrovert balanced by introvert, logic by intuition, entertainment balanced by artistry.”

Full Blast & Top Down: The Making of 1984 was written by John Scanlan (Author of Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock’n’Roll)