Story by John Scanlan (Author of Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock’n’Roll)

Story by John Scanlan (Author of Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock’n’Roll)

The singer, on one of his many exotic adventures, is lost in the Amazon rainforest weeks before the biggest gig the band will ever play. The guitarist is threatening to burn the master tapes of the new album, which is taking considerably longer than the usual five days to record. Drunken insults will be exchanged with The Clash at a festival supposedly celebrating brotherly love and togetherness. Yet, to the outside world, things appear more tranquil. Here are Van Halen, seemingly loved and loathed in equal measure; a roving gang of pranksters united in their desire to have fun in a world that takes itself too seriously – “like a buncha of gypsies yukking it up in the Foreign Legion,” as the singer would say.

And, as recent recipients of the highest fee ever paid to any performer – $1.5m for a drunken two-hour ramble through their best known songs that lands them in the Guinness Book of World Records – they have every reason to feel relaxed about the state of their world.

But now, in summer 1983, the seventies – and the loose life that decade had promised – seem finally, and belatedly, to be over. Suddenly the stakes have been raised. With MTV in the ascendancy, the record company now wants bona fide hits that will tear up the pop charts. So, it was just as well that here, on MCMLXXXIV/1984, Van Halen knew they had something big.

All they had to do was make it through to the fateful year that adorned their work-in-progress.

Hidden high in the Hollywood Hills, just a few miles from the more well-known rock’n’roll neighbourhood of Laurel Canyon, you will find Coldwater Canyon. Of the many Los Angeles canyons this was the one—so they say—where the really wealthy preferred to hide away from the noise of Hollywood. While Neil Young, Frank Zappa and other sixties icons pitched up in Laurel Canyon, the better off movie stars—Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston—retreated to Coldwater. As the road snakes up towards Studio City from Mulholland Drive, even the most eagle-eyed driver could miss a narrow passage that slips away to the right at one particular sharp bend. It quickly disappears into a tunnel of overhanging leaves and branches.

Here, in 1983, Eddie Van Halen would build a rudimentary 16-track studio, in an attempt to wrest control of the band that bore his family name from the guiding influence of David Lee Roth, the songwriting partner he would soon be comparing to world-renowned dictators like Idi Amin and Colonel Gaddafi.

While other people went looking for a home, Eddie – aka “Ed Van Halen, the Unabomber”, as David Lee Roth once called him – sought a hideaway. In the long dozen or so years since 1998’s poorly-received Van Halen III, there have been tales of fans making pilgrimages to that little road that slopes off Coldwater Canyon Avenue in search of nothing more than a security camera that might convey some message—PLEASE RELEASE SOME NEW MUSIC—in the hope that the reclusive guitar legend might see that there is still a world watching on the other side of the gate.

Such a lack of activity, of course, is understandable amongst men of a certain age – those who have seen better days and who perhaps still remain shell-shocked by the slow death of the record industry as they knew it. Yet, the waning of Van Halen also provides one big clue to their massive success in the late 70s and early 80s: namely, that they existed as the embodiment of an insatiable desire to live and play fast and loose. Even the cover of MCMLXXXIV/1984—adorned with the image of a mischievous sprite—suggested that this was a band that might experience some problems with the aging process. “I hate the word maturing”, Roth had told Rolling Stone in 1978. “I don’t like the word evolving, or any of that bullshit. The idea is to keep it as simplistic, as innocent, as unassuming and as stupid as possible.”

Such a lack of activity, of course, is understandable amongst men of a certain age – those who have seen better days and who perhaps still remain shell-shocked by the slow death of the record industry as they knew it. Yet, the waning of Van Halen also provides one big clue to their massive success in the late 70s and early 80s: namely, that they existed as the embodiment of an insatiable desire to live and play fast and loose. Even the cover of MCMLXXXIV/1984—adorned with the image of a mischievous sprite—suggested that this was a band that might experience some problems with the aging process. “I hate the word maturing”, Roth had told Rolling Stone in 1978. “I don’t like the word evolving, or any of that bullshit. The idea is to keep it as simplistic, as innocent, as unassuming and as stupid as possible.”

It was an attitude that meshed perfectly with Van Halen’s modus operandi in the years 1977-1982, with albums sometimes cut in mere days and – at most – weeks. In their initial demo sessions for Warners, their engineer Donn Landee recalled, the band cut “28 songs in two hours.” In an era when bands would often find themselves trapped in the studio, tinkering endlessly, producer Ted Templeman made sure his charges came to the studio already primed to lay down new material with minimum fuss. “All I have do,” he once said, “is stick a microphone in front of them.”

By the time of 1982’s Diver Down album, however, Eddie had decided that there had to be an end to Templeman and Roth’s fast-n-dirty approach to studio work. The haste with which the album was conceived and recorded was indicated by the fact that it cost less to make than their debut album. A sideways take on that album by Dave Queen, written in 2005, is not far short of how it was probably seen by Eddie: “Diver Down, where pothead singer David Lee Roth took over, included five cover versions—with its additional fragments, sketches, and impenetrable arcana, Diver Down is like an ‘unofficial’ Fall release or [The Beach Boys’] Smiley Smile.”

The real bugbear, though, was its cover of Martha and the Vandellas’ Dancing in the Street, a song chosen by self-confessed Motown freak, David Lee Roth. The song gnawed away at Eddie’s sense of creative freedom, made worse by the feeling that Templeman and Roth had “stolen” his original piece of music (the song’s inventive and pulsating Minimoog riff) to use on yet another cover tune. “I fucking hated that song. I never wanted to do it. That was the reason I decided to build my own studio.”

Roth, though, saw it all differently. The fact was that any cover tune they ever did, in his opinion, they owned—“Van Halenized”—in their own peculiar fashion. “A song’s a song,” he told Steve Rosen in 1980. “It’s the same thing as stealing hubcaps – pretty soon they’re on your car.”

The story of MCMLXXXIV/1984 really begins, however, on a spring day in 1982, shortly after the release of Diver Down, when Eddie showed up at Frank Zappa’s house in Laurel Canyon to meet the man who had recently thanked him for “reinventing” the guitar. It would turn out to be a more auspicious occasion than he could have ever imagined, as he got a close look at the well-kitted studio in the basement, which further emboldened him to begin building his own studio.

The story of MCMLXXXIV/1984 really begins, however, on a spring day in 1982, shortly after the release of Diver Down, when Eddie showed up at Frank Zappa’s house in Laurel Canyon to meet the man who had recently thanked him for “reinventing” the guitar. It would turn out to be a more auspicious occasion than he could have ever imagined, as he got a close look at the well-kitted studio in the basement, which further emboldened him to begin building his own studio.

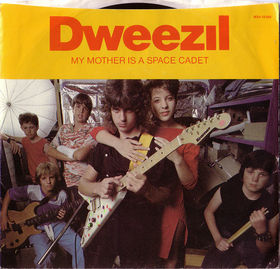

In Zappa’s studio, the two guitarists—along with Steve Vai, a Zappa band member at the time—jammed some tunes, as the twelve-year old Dweezil Zappa looked on amazed that Eddie had turned up wearing the jump suit he was pictured with on the sleeve of 1980’s Women and Children First album. As it happened Dweezil had been learning some choice Van Halen licks himself, courtesy of Steve Vai, which he practiced with his band, Fred Zeppelin.

Seeing as Van Halen weren’t due to go out on tour until July, Eddie ended up spending the best part of a month—during May and June ’82—driving over to the so-called “Utility Muffin Research Kitchen” (as Zappa’s studio was known) with Van Halen’s engineer Donn Landee, to produce a single titled My Mother is a Space Cadet for Dweezil and his little band of non-musicians. “We couldn’t play,” Dweezil recalled “and Eddie couldn’t figure out a way to get us to play together in time – so he just shouted ‘Go’, as if he was starting a kart race.” But, as was the case with Eddie’s previous non-band work, it was kept low-key, and the production would be credited to “The Vards”, a pseudonym chosen by Eddie and Donn Landee.

The presence of Landee was significant in everything that would unfold over the next year or so, as he stood shoulder to shoulder with Eddie in his determination to make the new record his way in a studio they would build together. The idea, Alex Van Halen said, was to build “a clubhouse where he could experiment at any time and where there wasn’t a clock running. The record company wasn’t thrilled about the idea, because they always think that bands are a bunch of drug addicts who need a babysitter. But we had the clout to do it.”

Asked some time later if the studio, which would be named 5150, represented a new phase of Van Halen, Eddie said that it was more like “Phase One of Donn and Ed. Donn and I were very involved in this record. We almost took control, to a point, because it was done here in our studio, and we knew what we wanted. We weren’t about to let the album be puked out in any way—especially since it was done here.”

With Landee back in Los Angeles assembling gear for the studio—including an old 16-track console about to be thrown out by United Western Studios that had been used on sessions by the likes of The Beach Boys and The Mamas and the Papas—Van Halen took to the road in July 1982, hitting Atlanta, Georgia for the first show of a scheduled 90-date jaunt that would finish in mid-December in Jacksonville, Florida, before swerving down to South America in the New Year.

Eddie’s first—and probably unintended—blow against Roth, however, occurred during a tour break in October, when he found himself entertaining Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones who had turned up at his house in the hope that they could persuade him to play on a driving guitar tune they wanted to cut for Jackson’s new album, Thriller. It was conceived as something along the lines of My Sharona, a huge hit for The Knack in 1979. As he banged out a rhythm on one of Eddie’s guitar cases, Jackson sang the tune to give the guitarist an idea of what they had in mind. Eddie agreed he’d do it, but insisted on bringing his own equipment and Donn Landee—it was the only way he would get his sound.

At the comparatively plush surroundings of Westlake Studio in Santa Monica, Eddie would soon be knocking back a few beers that were thoughtfully provided by Quincy Jones, who figured it would help the guitarist loosen up. After listening to the backing track a few times to get a feel for the song, all Jones said was, “okay, do your thing.” Eddie let rip on a couple of takes, which were so loud that the session engineer, Bruce Swedian, left the studio covering his ears, leaving behind Donn Landee to man the board. On the final run through, though, as Eddie was playing the last notes of the solo—which attain the whizz-bang of a firework—one of the studio monitors promptly blew up and caught fire. As Quincy Jones’s song-writing partner Rod Temperton later recalled, the people at the session could only look on in amazement at the flaming speaker, as if it was some kind of omen: “we were all there looking at this, thinking—this must really be something!” It was something—but also something the rest of Van Halen didn’t want to hear.

Some five months later David Lee Roth had just returned from a six-week trip through the Amazon, during which he and his bodyguard Ed Anderson—lost and out of contact—were reduced to improvising an existence as they drifted from one nowhere to the next. “A million miles up the dead-empty Amazon river,” Roth recalled in his autobiography, “it’s like every book you ever read. Ed’s making an omelette out of a can of what we think is Spam but in Portuguese is dog food. There was no picture [on the can]. We’re shopping up stuff in open-air markets, this is total pirateville.”

Setting off for Brazil after the last Van Halen show in Buenos Aires, Argentina on 11 February, 1983, Roth could have had no idea that the press would, in a matter of weeks, be reporting that he had vanished without a trace. British tabloid, The Sun, adopted a gleeful tone in breaking the news on 3 March: “Good news for music lovers everywhere. David Lee Roth, the ridiculously macho singer with heavy metal band Van Halen, has been lost up the Amazon!”

But, back in Los Angeles—musing on his good fortune in not actually being dead—a radio blaring from a nearby car delivered a bolt-like shock. “The new Michael Jackson song ‘Beat It’ came on,” Dave recalled later. “I heard the guitar solo, and thought, now that sounds familiar. Somebody’s ripping off Ed Van Halen’s licks.”

“Believe it or not,” Eddie told Guitar World in 1990, “I did the Michael Jackson thing ‘cause I figured nobody’d know. The band for one—Roth and my brother and Mike—they always hated me doing things outside of Van Halen. I just said ‘Fuck, I’ll do it, and no one will ever know.’ So then it comes out and its song of the year and everything.”

End of Part 1. Check out Part 2!