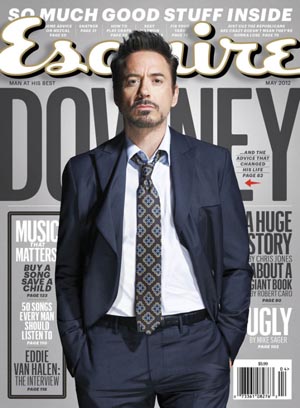

From Esquire.com:

He started playing, and millions of teenage boys started banging their heads against the wall. Thirty-five hard years later, he’s got a new album, a new tour, and his kid Wolfgang is in the band. What would you give to play Eddie’s guitar backstage at the Garden?

BY DAVID CURCURITO

I’m shaking this man’s hand and it feels like my Uncle Charlie’s, who swung a hammer all his life. Fingers of iron and forearms of steel, like Popeye. If Charlie pointed one of those rebar fingers at you, he meant some serious goddamned business. Same thing with this guy. Dude’s knuckles look like knots in an old oak tree and his fingers are ripped. A workingman’s hand, engineered for manual labor, not for something so fine as music. And that voice, cured with smoke and drenched in Scotch. It’s that voice you hear at the end of your favorite Irish bar in Hell’s Kitchen, always three drinks in, no matter the time, day or night. I’m not a drunk anymore, but since they cut out my tongue, I sound drunk. The cancer got a portion of his tongue and attacked his throat, too. But to hell with all that, this guy is still alive, and we’re backstage at Madison Square Garden in his dressing room about an hour before the show.Eddie Van Halen takes a deep drag on his electronic cigarette. Sit down on that couch, over there. He rifles through a stack of guitar cases, all guitars of his own making. He wants to show me a special one. The room is comfortable, with a couple of couches facing each other, a nice Oriental rug on the floor, a healthy food spread, a tub of drinks on ice. No alcohol, absolutely no alcohol allowed backstage, he is done with alcohol. It’s like, God gave me one big bottle and I drank it all. I’m done.Me, I’m dying for a beer. Some people are religious pilgrims, running all over to see a miracle. But this is as close to holy as I’m ever going to feel, Eddie Van Halen’s dressing room at the Garden, and I think he’s about to bless me with his guitar, and I need a beer. I had the Eddie Van Halen hair when I was a kid, and I watched his every move, and I even had a guitar — how hard can it be? It took me an unseemly amount of time to realize that I wasn’t him and wasn’t ever going to be him, but something deep inside still wants to think there’s a chance that I was wrong. My face hurts from smiling, and I can’t stop saying, “This is great, this is great, this is great.” I’m sitting across from his wife of three years, Janie, who’s a good-looking woman, great body. Before she was leader of Camp Van Halen, she was a ground pounder … a stuntwoman. She would do bar fights, get hit by cars, fall out windows, rappel down buildings. Her voice is straightforward and commanding. She’s clearly on guard and she should be — she saved his life and she’s not going to let anyone screw it up, least of all Eddie himself. A tiny orange Pomeranian named Kody is jumping up and down on my leg while Ed — Janie calls him Ed — looks for that guitar. The motherfking guitar. The guitar that changed the world, the guitar that sits in the Smithsonian Institution with Einstein’s pipe and Thomas Jefferson’s Bible, the guitar he wasn’t even supposed to play. When his family hopped on a boat from the Netherlands to Pasadena in March 1962, they didn’t have much at all — fifty bucks, a couple of bags … and a piano. Who brings a piano on a boat? We actually played music on the boat on the way over here, you know? I’m serious! It wasn’t like, “So what do you want to do in life?” Dad said, “We’ve got to make a living.” So if it weren’t for music, we wouldn’t have survived. But in America, you play guitar, because in America you’ve got your Van Cliburns and your Van Halens, and the Van Cliburns don’t get to be rock stars.His father was a professional musician once he got to L. A., which meant he worked as a janitor. As Ed looks through the stack of cases, he’s looking for the guitar that changed his family’s life when they had to dumpster-dive for scrap metal for a few extra bucks. Ed was a natural, but he was impossibly shy and he’d get so nervous when he had to face even the smallest audience that you’d see his whole body jangling, and so when he was twelve, his dad gave him a shot of vodka and a Pall Mall to ease his nerves, and started him on a lifetime of playing drunk. There are whole tours that Ed barely remembers. Hey, he had to make a living. There was no thought given. It wasn’t like, “What are your dreams?” I never dreamt of being a musician for my livelihood. I certainly never would have wanted to be in the business that I’m in, meaning the fame and the glory, the glitter, the rock star, the famous part.First he played with his father, with his brother, Alex, on drums. And later, when the brothers were doing gigs at Gazzarri’s on the strip and their father would be playing a bar mitzvah or a wedding in Oxnard, the three of them would meet up after. Two, three in the morning in the back of Ed’s van, just drinking and disturbing the neighbors. My mom’s just going fucking crazy.”Get your ass in here!” She’d lock us out and we’d have to break a window to get in. She hated the fact that we were into music. She wore the pants in the family. I hate to say it, but I don’t think my dad would have drank as much as he did if it wasn’t for her. She had a heart of gold, and don’t take this the wrong way, but Hitler on a bad day, whoa.

It’s funny, his dear old mom, God rest her soul, would do the air-guitar thing and tell her son, “Oh, you’ll never get anywhere going boom, boom, boom, jing, jing, jing. When are you going to get a real job?” “You watch, Mom. We’ll go somewhere one of these days.” We get signed to Warner Brothers and she goes, “Now how long will that last?”And then he changed rock ‘n’ roll forever.

Actually, he and his guitar knocked it right on its ass around 1978, when punk was cutting itself with razors and disco was … mother of God, check out this Top Ten from Billboard, 1978: 1. “Shadow Dancing,” Andy Gibb; 2. “Night Fever,” Bee Gees; 3. “You Light Up My Life,” Debby Boone; 4. “Stayin’ Alive,” Bee Gees; 5. “Kiss You All Over,” Exile; 6. “How Deep Is Your Love,” Bee Gees; 7. “Baby Come Back,” Player; 8. “(Love Is) Thicker Than Water,” Andy Gibb; 9. “Boogie Oogie Oogie,” A Taste of Honey; 10. “Three Times a Lady,” Commodores. And when the world heard “Eruption,” Ed’s one-minute, forty-two-second assault, with its dive bombs and furious precision picking, teenage boys everywhere started pounding their heads against a wall. That guitar.

Ed finds the case he’s been looking for, and without thinking, I stand up and walk over to where it rests and kneel before it. Not in a religious way — like I said, I’m not religious. I just want to get a good look. Ed walks over and kneels down next to me. He pops the three latches one by one, pop, pop, pop, then he opens it. This is the guitar that contains the latest of several patents that Ed holds — things that he saw in his head that he needed to play the way he wanted to play but didn’t yet exist. He’s probably the greatest guitar engineer since Les Paul, makes his own line now called Wolfgang — named after his son and some other guy — and this guitar is the culmination of all of his thinking. Les and I used to always talk about the reasons that we built things. One day I’m hangin’ with him, and we both flip out a pick and we both have sandpaper Krazy Glued to them. We had the same problem, you can’t hold on to ’em. Everything that we do is not for the sake of creating something but because nobody else makes it. It’s like “I need this in order to do that.” Okay, there. It works.

The instrument’s body is beautiful like a woman’s hips, with two devil horns at the top where his hands hit the upper register of the fret board. It is amber and tobacco-brown-red, and it glows like something sacred when the light hits it. Its neck is unfinished bird’s-eye maple, stained with the sweat and oil from Ed’s hands. When that stain sets in from playing it a whole bunch, there’s nothing like it. It’s just smooth and perfect. He’s saying this and I’m thinking they should put a tap in him and sell that shit. Eddie Van Halen’s Essential Oils! Makes you play better instantly! After all his years of partying, it’s probably 100 proof. Like everything else he does, it would sell, too.

Everybody’s got things that make their lives worth living. We all start out with insane enthusiasms that are tempered by age or suppressed for appearances. I mean, you can’t be an asshole, you know? You have to grow up. Some famous guy said that all of us are born originals, but most of us die copies. But what if you’re the guy everybody copies? What if somehow you get to be the original? Whatever you think of his music, that has been Ed Van Halen’s lot in life. Over all his years, millions of young men would watch his every move. Led by me. I’d memorize him, trying to catch any kind of clue. Because in the beginning, Ed didn’t have the shiny new guitar in the perfect red velvet case. He couldn’t afford it, so he built his own. You couldn’t buy what he had because it didn’t exist. There was a certain mystery behind his creation. The guitar, the one that hangs in the Smithsonian, that’s an exact replica of the one he built. Nicknamed by fans, it’s called Frankenstein and it’s a mess of a guitar. A variety of pieces and parts slapped together over the years. A paint job so nuts, black and white and red crisscrossing, there’s no way anyone would dare copy it. What’s that, a quarter he put under the tailpiece? Have you heard the front pickup doesn’t even work, it’s just there for no reason! When I was a kid, I heard he boiled his strings; by God, I boiled my strings, too. Why did I boil my strings? Only the wound ones. Right. No, I was boiling them all. Only the wound ones, because dirt gets in the windings. It saves, you know, it saves a lot of money. He’s probably the only one who could get a halfway decent sound out of that piece-of-shit guitar. Where’s the original? I ask, and he and Janie look at each other then back at me like I’m asking Janie to show me her underwear. We can’t tell you where the original is. It’s somewhere safe. Ed’s old Marshall amp? Same thing. His sound was called the brown sound and it was mythical. People were always trying to figure it out. And everybody suspected that he was using some kind of magic.

It’s all in the fingers, man. He tells a story about when the band first hit. Van Halen was opening for Ted Nugent back in 1978 at the Capital Centre. Ted was cool enough to give the band a sound check. He’s standing off to the side and he’s listening to me, and he comes up and says,”Hey, you little shit! Where’s your little magic black box?” I’m going, Who the fuck is that? And it was Ted. Hey Ted, it’s nice to meet you, thanks for the sound check. And he’s going, “Let me play your guitar!” I go, “Okay, here you go.” He starts playing my guitar and it sounds like Ted. He yells,”You just removed your little black box, didn’t you? Where is it? What did you do?” I go, “I didn’t do anything!” So I play, and it sounds like me. He says, “Here, play my guitar!” I play his big old guitar and it sounds just like me. He’s going, “You little shit!” What I’m trying to say is I am the best at doing me. Nobody else can do me better than me.

You know, Eric Clapton is Eric Clapton. Nobody does Clapton better than him. Nobody does Hendrix better than Hendrix. We’re not trying to be anything other than who we are.

We’re still on our knees, and Ed picks up his guitar, thumbs around in his pocket for one of his custom picks, and starts playing. His hands move up and down the neck of the guitar with ease. He’s just dicking around, beautifully playing nothing in particular, and I just can’t take my eyes off the guitar. He demonstrates the new piece of equipment he made for this model, a gadget that allows you to switch the tuning with the flip of a metal bar. He calls it Drop to Hell, D2H for short. It’s shiny, clean, and housed within a cavity carved out of the guitar’s tail — it looks like something you might see used in surgery. At this point, I just can’t help myself and unconsciously extend both hands in Ed’s direction. “Can I try?”

The thing is, Eddie Van Halen should never have set foot on a stage. He’s never really talked about it, but this album is the first album he recorded sober, and this tour is the first tour that he will fully remember. For thirty-five years his nerves just paralyzed him, and the bottle was his only cure. It’s funny, I was doing a little bit of thinking why I’m always nervous, especially during interviews, because I rarely do interviews. And for one, a lot of people, just when I was growing up in school, people thought I was an asshole, because I didn’t have much to say, you know what I mean? You know, the quiet guy. And it’s just because I was shy. The funny thing is, about the whole alcoholism thing: It wasn’t really the partying. It was like — I don’t mean to blame my dad, but when I started playing in front of people, I’d get so damn nervous. I asked him, “Dad, how do you do it?” That’s when he handed me the cigarette and the drink. And I go, Oh, this is good! It works! For so long, it really did work. And I certainly didn’t do it to party. I would do blow and I would drink, and then I would go to my room and write music.

When Van Halen hit big, everybody expected the guitar player to be able to talk, but Ed just shit himself during his first radio interview in San Jose. And here we were on live radio, and the guy’s going, “We have Van Halen, a brand-new band from L.A. here in the studio. So Dave, tell me” … And here’s Dave, “Bop, bop, yabba, dabba, doo,” you know? Then he turns to me and says, “I understand you and your brother, Alex, are from Amsterdam, Holland.” And I went, “Yeah.” Dead air. And the poor disc jockey starts gesticulating like crazy, pantomiming Whaddya mean, Yeah? Don’t you know, like, any more words you might say right now? And I’m looking at him, and I start gesticulating, too, and then I say, out loud, “What the fuck does this mean?” It was a fuckin’ disaster. Roth told him that to be interesting, he should just make stuff up. Dave said, “Here’s what you’re gonna do. You’re gonna lie.”

Ed would eventually hit a wall, over and over again, and he assumed that he would just die. The band hit big, but if his playing was brilliant, his drinking was spectacular. And a few years ago, he actually started falling apart. Too many years of jumping around stage had ruined his hip, requiring a new titanium model. Up to this point, self-respecting rock stars had had the decency to drown in their own vomit, not living long enough for their hips to stop working. But Ed’s parts were wearing out, and men of a certain age all over the country felt a twinge, too. Of course, Ed had what it took to die of drink, too. As a drunk, he was no slouch, man.

Thank God he met Janie Liszewski. She met Ed at a time he says was his absolute worst, 2006 or so. She was doing PR for a film-production company and he just happened to be doing the soundtrack for one of their films. Ed wanted to stop drinking yet again. She didn’t force him, because you can’t just force someone. Man, if you ever get to see Janie, you know she cleaned house for this guy. She wasn’t putting up with any bullshit. He had done a bunch of rehabs in the past, a month here, a month there. But this time he went to stop drinking once and for all. The doctors put him on a horrible drug called Klonopin. Then while onstage, he took a nosedive and had to go to rehab to get off the Klonopin, and they put him on antidepressants. Ed’s system was in such shock that he became catatonic for about a year and spent most of 2008 watching television. Fucked me up, you know? All I wanted to do was stop drinking. But instead I literally could not communicate. Yeah, I was gone. I don’t know what dimension I went to, but I was not here. The doctors didn’t know if he was going to come out of it normal. Janie’s freaking out, had to get him off the goddamned pills, and it took a while. It was such a long process to come out of this. Just to be able to communicate, to talk, was a feat in itself. You know when you see homeless people and they’re literally not here, you know? I laid on the couch for a year. Just watching Law & Order. I was always in the studio making music, and now, nothing. And his brother, Alex, was by his side, he’s there checking on his little brother with love and support, making sure he doesn’t just walk off.

The doctors helped me out with this amino-acid treatment stuff, or whatever it was. And slowly I came out of it, and the first thing I remember, really, was picking up a guitar, and my whole hand was locked into a fist. And I thought, “Okay, I guess I won’t be playing anymore.”

This time he had no program. The program doesn’t work for Ed. You know, people say with that twelve-step program you will succeed. I disagree. When they say, “You can’t say, I will never drink again,” I can honestly say I will never drink again. It’s a whole new world. I’m fifty-seven years old and I know I’m not going to live to be 114, so I can’t say I’m halfway done. It’s a sullen truth, but this is the first record I’ve made sober. There’s a certain place that you have to get to where things just flow, and I have to say that when I drank and did blow, it might have created a false sense of getting there easier. I’m not comparing myself to all these famous artists in history, but you know, everybody, guys like Mozart, they were all alcoholics. And it does somehow enable you to lower your inhibitions. At the same time, it also gives you a false sense that what you’re doing is great. Now I’m so aware of everything that sometimes I’m afraid to pick up my guitar.

It turns out that he did it for his kid.

A few days earlier, I was at the band’s sound check in an empty Madison Square Garden. There’s Ed, his brother, Alex, who is just sunglasses behind the shiny rack of drums in front of him, sticks flailing. And there’s Wolfgang Van Halen, who is now twenty-one, on bass. David Lee Roth isn’t around, he doesn’t do sound check, and that’s all right with the Van Halens. Lots of eye rolling happens when the subject of Roth comes up. I’m not saying the lead vocal detracts, but in general the first thing people focus on is the vocal. But vocals aside, there’s a lot of shit going on that you’re missing. You know what I mean? [Hums opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth.] You can’t be singing to that — you’d ruin it, right? What the hell could you sing to that?

Between songs Wolfgang is belting out orders. “Let’s try that again after the solo. Dad, you keep forgetting that part… Okay, I’d like to run through ‘Full Bug’ and then go into ‘Girl Gone Bad.’ ” It’s just the music and background vocals, and it’s really tight. With the old songs it was bass player Michael Anthony’s ultrahigh harmonies that really gave Van Halen its signature sound, and Wolfie doesn’t miss a note. He’s actually a great singer. Occasionally he’ll sing Roth’s lines just to fill in the sound, maybe to cue his dad to the song’s musical changes. After the sound check, I’m sitting in Ed’s dressing room and Wolfgang pops in. He’s a tall guy, stocky with a boyish face. He looks more like his mom, Valerie Bertinelli, than he does his father. Introductions are made and he looks me right in the eye with a firm handshake. He takes after me, Ed says. Wolf grabs a seat and starts talking about the set list. Hey, whatever you want to do, Wolf, just make sure everyone gets the list, so we know what the hell we’re doing tonight. Wolfgang joined the band when he was just fifteen, and in addition to playing bass, he has also become the field marshal who makes all of this work. For the new album, his first album ever, the band pulled songs from demos they’d made back before they’d been signed to a record deal, way before Wolfgang was born. But it was the kid who picked the songs that would work on the album, and the band went for it.

He was fifteen when he joined the band. It wasn’t easy to convince his mother. Oh, that was hell. Look, I’m tellin’ you, she’s like my mom. Yeah, I pulled him out of school. She’s like, “You’re not doing that.” I’m like, “Jodie Foster, she went to school later and she’s okay. Trigonometry doesn’t apply to music anyhow.” Ed recalls when he bought Wolf his first drum set, the drums sat in a room upstairs for months and months, collecting dust. Then one day, he heard unbelievable footwork with the bass pedal coming from upstairs. All of a sudden, he’s doing stuff with one foot that I can’t as a drummer do with two feet. So I ran down to the bedroom where his mom was and I said, “Do you hear that?” She goes, “Yeah. Yeah.” Right then and there, she knows. That was it. Ed says that he was really concerned when Wolfgang was born because Bertinelli’s father had no rhythm whatsoever, You know, kind of like Navin Johnson in The Jerk. Thank God almighty, thank God, Wolfgang had rhythm.

When Wolfgang was twelve years old, Alex and Ed were working together in the studio. Ed had hung a rug up over the studio window so his brother couldn’t see who was playing bass with him. Wolf came along and his father quietly told him to pick up the bass and play along with him. And he did, flawlessly. When the song was through, Alex, knowing his brother obviously wasn’t playing both guitars, said, “Who was that?” A little voice comes over the console. “Hi, Uncle Al. It’s me, Wolfie.”

I mean, it’s kind of like learning how to ride a bicycle, I guess. You kind of coach him and before you know it, he’s on his own. We were sitting there, and we’re like, “We need a bass player. You feel like playing bass?” And before you know it, he’s in the band. I didn’t really give him — I didn’t really ask him, What do you want to do in life? You know? Just like my father didn’t, either. I just said, “Why don’t you play bass?” “Well, okay.” “Hey, Wolf, you wanna go on tour with us?” “Yeah, sure, why not?” He blows my fuckin’ mind, man. We never knew where it would end up.

When Van Halen reunited with Roth in 2007 for a North American tour, Wolfgang was on bass. He was sixteen and getting a shit ton of flack from fans for replacing Michael Anthony. I mean, what a crazy situation to put a sixteen-year-old through — talk about hit the ground running. But without Wolfgang, the 2007 reunion wouldn’t have happened. The new album and 2012 tour wouldn’t have happened. I ask Ed what his father would have made of Wolfgang, and the question throws him a little, his voice shakes and his eyes go moist. Oh, God, don’t make me cry… Sometimes I think Wolfie’s him, reincarnated. He would have been so proud.

I never meant to hurt anyone, you know?

Everything’s changed now, everything. He even has to find a new place to write, because the classic studio where Ed has made many of the Van Halen records since his sound first hit the earth like a meteor — 5150 they called it — brings back all the bad memories of drugs and booze. It’s not a sanctuary like it used to be. I still love it as a recording studio, it’s a great sounding room, but I need a place where I can go that’s not so full of the past.

Some things never change, though: Thirty-five years in, Ed’s nerves won’t leave him alone. For the new record, A Different Kind of Truth, Ed recorded at Henson Studios in Hollywood. I play a solo, and afterward I was literally shaking. Everyone’s going, “Are you all right?” And I go, “I’m fucking nervous.” “Yeah, but you’re Eddie Van Halen,” they say. And I go, “I know who I am, but I’m still nervous.”

Back in the dressing room, Ed takes a couple of long draws from his electronic cigarette and blows out a huge cloud of vapor. You’d swear it was real smoke, but he had to quit that, too. In 2000, he felt a callus on his tongue, a patch of dead skin caused, he figured, by the way he chewed his food or some shit. When it was discovered to be cancer, Ed concocted elaborate theories — it was from the metal in his titanium hip, or from chewing on his custom copper pick while standing in a studio filled with electromagnetic waves. The four hundred packs of cigarettes a day, the booze and cocaine, had nothing to do with it. The doctors had him drink an experimental radioactive rinse, then they cut out a piece of his tongue shaped like the end of his pick. And he was cancer-free until last year, when he got hit twice. I haven’t talked about this, because I don’t talk about this. Last spring, doctors found cancer cells in his throat and took a scalpel to them. Last fall, the cancer came back and they took another chunk of his tongue. Every few months, he opens his mouth and doctors poke at him.

And I have to say, he is the healthiest fifty-seven-year-old I’ve ever seen. He looks young and vital and happy, lean and muscled, and his playing has never been better. So the news he’s just broken of the recent revenge of the cancer makes no sense to me, and at the same time makes his appearance, this tour, this band, all the more miraculous.

Then Ed hands me the guitar and I cradle it like a newborn. I just stare at it for a long time, before gingerly beginning to play. He’s calling out chord changes to me so I can use it the way he intended. I’m not religious, dammit, I’m not. But I’m starting to believe.