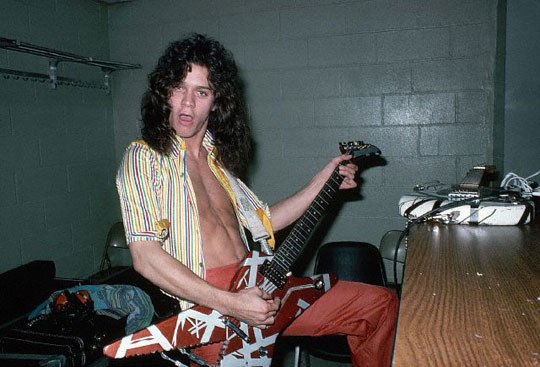

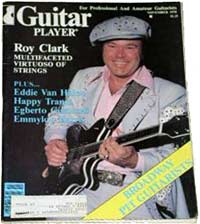

Last week the VHND featured the story of how Jas Obrecht scored an interview with Eddie Van Halen during the band’s first world tour. Here is the interview as published in the November 1978 Edition of Guitar Player magazine:

“Heavy-Metal Guitarist from California Hits the Charts at Age 21”

By: Jas Obrecht

Edward Van Halen’s clean, powerful lead playing was first recorded earlier this year on his band’s predominately heavy-metal debut album, Van Halen [Warner Bros.]; at the time he was 21. Eddie imigrated to the U.S. from the Netherlands during the rock and roll heyday of the late ’60s and soon abandoned his piano for drums and electric guitar. He spent years playing small clubs, beer bars, backyard parties, and dance contests, collecting the band’s current lineup along the way. Van Halen’s discovery in March 1977-described by Eddie as “Something right out of the movies”-came one night when Mo Ostin, then president and chairman of the board of Warner Brothers, and producer Ted Templeman saw their act at the Starwood club in Los Angeles. With Eddie’s brother Alex on drums, Michael Anthony on bass, and lead singer Dave Lee Roth, the band recorded 40 songs in three weeks, including “Running with the Devil,” a searing guitar solo aptly titled “Eruption,” and a remake of the Kinks’ classic “You Really Got Me.” Eddie joined the legion of musicians on the road when Van Halen embarked on a nine-month tour in February. Eddie was born in Holland on January 26, 1957. His father, a professional saxophonist and clarinetist who played live radio shows, got Eddie and Alex interested in playing music at an early age. “We both started playing piano at age six or seven,” Eddie recalls, “and we played for a long time. That’s where I learned most of my theory. We had an old Russian teacher who was a very fine concert pianist; in fact, our parents wanted us to be concert pianists.”

Eddie was born in Holland on January 26, 1957. His father, a professional saxophonist and clarinetist who played live radio shows, got Eddie and Alex interested in playing music at an early age. “We both started playing piano at age six or seven,” Eddie recalls, “and we played for a long time. That’s where I learned most of my theory. We had an old Russian teacher who was a very fine concert pianist; in fact, our parents wanted us to be concert pianists.”

In 1967 the Van Halens moved to the U.S., and Eddie got his first taste of rock and roll. “I wasn’t into rock in Holland at all,” he says, “because there really wasn’t much of a scene going on there. When we came to the U.S. I heard Jimi Hendrix and Cream, and I said, ‘Forget the piano, I don’t want to sit down-I want to stand up and be crazy.’ I got a paper route and bought myself a drum set. My brother started taking flamenco guitar lessons, and while I was out doing my paper route so I could keep up on the drum payments, Alex would play my drums. Eventually he got better than me-he could play ‘Wipe Out’ and I couldn’t. So I said, ‘You keep the drums and I’ll play guitar.’ From then on we have always played together.”

Eddie bought himself a Teisco Del Ray electric guitar-“a $70 model with four pickups”-and began to copy licks off of records. “My main influence was Eric Clapton,” Eddie says. “I realize I don’t sound like him, but I know every solo he’s ever played, note-for-note, still to this day. My favorites were the Cream live versions of ‘Spoonful’ [Wheels of Fire, RSO] and ‘I’m So Glad’ [Goodbye, RSO]. I liked Jimi Hendrix, too. But now no one in Van Halen really has one main thing that he likes. Dave, our singer, doesn’t even have a stereo; he listens to the radio, which gives him a good variety. That’s why we have things on the Van Halen album that are a change from the slam-bang loud stuff-like John Brim’s ‘Ice Cream Man.’ We are into melodies and melodic songs. You can sing along with most of our tunes, even though many of them do have the peculiar guitar and the end-of-the-world drums.”

Eddie and Al Van Halen formed their first bands while attending high school in the suburbs of Los Angeles. During the early ’70s they teamed with a bass player to form Mammoth, the last band they played in before forming Van Halen. “I used to sing and play lead in Mammoth,” Eddie explains, “and I couldn’t stand it-I’d rather just play. David Lee Roth was in another local band, and he used to rent us his PA system. I figured it would be much cheaper if we just got him in the band, so he joined. Then we played a gig with a group called Snake, which Mike Anthony fronted, and we invited him to join the band. So we all just got together and formed Van Halen. By the time we graduated from high school everyone else was going on to study to become a lawyer or whatever, and so we stuck together and started playing in cities in California-Pasadena, L.A., Arcadia. We played everywhere and anywhere, from backyard parties to places the size of your bathroom. And we did it all without a manager, agent, or record company. We used to print up flyers announcing where we were going to play and stuff them into high school lockers. The first time we played we drew maybe 900 people, and the last time we played without a manager we drew 3,300 people.”

The band worked on their own material and got gigs playing Southern California clubs and auditoriums, including the Santa Monica Civic, the Long Beach Arena, and the Pasadena Civic Auditorium. Soon they where working as the opening act for performers including Santana, UFO, Nils Lofgren, and Sparks. Their appearance at the Golden West Ballroom in Norwalk, California, brought them to the attention of Los Angeles promoter Rodney Bingenheimer, who booked them into the Starwood. They played the club for four months, and there met Gene Simmons, Kiss’ bass player, who financed their original demo tape sessions. “We made the tape,” Eddie says, “but nothing really came out of it because we didn’t know where to take it. We didn’t want to go around knocking on people’s doors, saying, ‘Sign us, sign us,’ so we ended up with just a decent sounding tape.” While playing the Starwood, the band also came to the attention of Marshall Berle, who would eventually become their manager. It was through Berle, Eddie explains, that the band had its fortuitous meeting with Ted Templeman and Mo Ostin: “We were playing the club one rainy Monday night in 1977, and Berle told us that there were some people coming to see us, so play good. It ended up that we played a good set in front of any empty house and all of a sudden Berle walks in with Ted and Mo Ostin. Templeman said,’ It’s great,’ and within a week we were signed up. It was right out of the movies.”

Van Halen entered the studio, and within three weeks they emerged with enough material for at least two albums. “For the first record,” Eddie recalls, “we went in to the studio one day and played live and laid down 40 songs. Out of these 40 we picked nine and wrote one in the studio–‘Jamie’s Cryin’.’ The album is very live–there are few overdubs, which is the magic of Ted Templeman. I would say that out of the ten songs on the record, I overdubbed the solo on only ‘Runnin’ with the Devil,’ Ice Cream Man,’ and ‘Jamie’s Cryin”-the rest are live. I used the same equipment that I use onstage, and the only other things that were overdubbed were the backing vocals, only because you can’t sing in a room an amp without having a bleed on the mikes. Because we were jumping around, drinking beer, and getting crazy, I think there’s a vibe in the record. A lot of bands keep hacking it out and doing so many overdubs and double-tracking that their music doesn’t sound real. And there are also a lot of bands that can’t pull it off live because they have overdubbed so much stuff in the studio that it either doesn’t sound the same, or they just stand there pushing buttons on their tape machines. We kept it really live, and the next time we record it will be very much the same.

“The music on Van Halen took a week, I would say, including ‘Jamie’s Cryin”-I already had the basic riff for that song. My guitar solo ‘Eruption,’ wasn’t planned for the record. Al and I were picking around rehearsing for a show, and I was warming up with this solo. Ted came in an said, “It’s great, put it on the record.” The singing on the album took about two weeks.”

Eddie’s strategy within the band, he says, is “I do whatever I want. I don’t really think about it too much-and that’s the beauty of being in this band. Everyone pretty much does what they want, and we all throw out ideas, so whatever happens, happens. Everything is pretty spontaneous. We used to have a keyboard player, and I hated it because I had to play everything exactly the same with him. I couldn’t noodle in between the vocal lines, because he was doing something to fill it up. I don’t like someone else filling where I want to fill, and that’s why I’ve always wanted to play in three-piece bands.”

Eddie assembled his main guitar with parts he bought from Charvel. “It is a copy of a Fender Stratocaster.” He says. “I bought the body for $50 and the neck for $80, and put in an old Gibson PAF pickup that was rewound to my specifications. I like the one-pickup sound, and I’ve experimented with it a lot. If you put the pickup really close to the bridge, it sounds trebly, if you put it too far forward, you get a sound that isn’t good for rhythm. I like it towards the back-it gives the sound a little sharper edge and bite. I also put my own frets in, using large Gibsons. There is only one volume knob-that’s all there is to it. I don’t use any fancy tone knobs. I see so many people who have these space-age guitars with a lot of switches and equalizers and treble boosters-give me one knob, that’s it. It’s simple and it sounds cool. I also painted this guitar with stripes. It has almost the same weight as a Les Paul.”

Eddie’s other guitars include an Ibanez copy of a Gibson Explorer, which, he says, “I slightly rearranged. I cut a piece out of it with a chainsaw so that it’s now a cross between a [Gibson Flying] V and an Explorer, and I put in different electronics and gave it a paint job. I’ve also recently bought a Charvel Explorer-shaped body and put a Danelectro neck on it and an old Gibson PAF pickup. And I also found a 1952 gold-top Les Paul. It’s not completely original-it’s got a regular stud tailpiece in it, and a Tune-o-matic bridge. I have rewound Gibson PAF pickups in it, too. I use a Les Paul for the end of the set because my Charvel is usually out of tune, and the Les Paul’s sound is a little fatter.

“Nobody taught me how to do guitar work: I learned by trial and error. I have messed up a lot of good guitars that way, but now I know what I’m doing, and I can do whatever I want to get them the way I want them. I hate store-bought, off-the-rack guitars. They don’t do what I want them to do, which is kick ass and scream. Take the vibrato setup, for example. You have to know how to set it up so it won’t go out of tune, which took me a long time to get down. It has a lot to do with the way you play it-you can’t bring it down and not bring it up. Some people just hit the bar and let go-you have to bring it back right. Sometimes you’ll stretch a note too far with your fingering hand, and it’ll go flat. Here you have to pull the bar up to get it back to normal. I’ve also found that gauged set of strings will work better than one you make up. Like, I used to use heavier bottom strings with light top strings, and it didn’t work very well. I also buy a different spring from Fender for my vibrato-one that’s a little looser-and this makes a big difference. You also have to watch out for the little string retainers Fender uses, because sometimes the strings can get caught in them and go out of tune.”

Onstage, Eddie uses an Univox echo unit that is concealed in a World War II practice bomb. “I had a different motor put in it,” he says, “so it would delay much slower and go really low. I use this for ‘Eruption.’ I also use two Echoplexes and a flanger for subtle touches. And I use an MXR Phase 90 phase shifter that gives me treble boost for solos, too.”

On a recent return flight from Japan, Eddie’s original 100-watt Marshall amps were lost in air freight, and he’s replaced them with Music Mans, Laneys, and new Marshalls. “I like three 100-watt amps for the main setup,” he says. “After I do my guitar solo I change guitars and amps to the second setup, and the third setup, also three amps, is for back-up. I have each guitar plugged into a different setup so that if anything goes wrong all I have to do is grab another guitar. This saves my worrying about trying to fix the amp. I use voltage generators, which can crank my amps up to 130 or 140 volts. Amps sound like nothing else to me when they are cranked so high, but you have got to keep a fan on them because they blow so often. You have to retube them every day, and they usually don’t work for more than ten hours of playing.”

Eddie seldom formally practices with his guitar, preferring instead to “play when I feel like it. But I am always thinking music,” he says. “Sometimes people think I’m spacing off, but really I’m not. I am always thinking of riffs and melodies. Lately I’ve thought up acoustic-type riffs.”

Nine months on the road has given Eddie a fair share of experiences, but it hasn’t altered his feelings about rock and roll. “I have never given up on rock,” he says. “There are people out there who used to say that rock is dead and gone-bullshit. It has always been there, and it is still the main stadium sellout thing. If you want to be a rock guitarist you have to enjoy what you are doing. You can’t pick up a guitar and say, ‘I want to be a rock star’ just because you want to be one. You have to enjoy playing guitar. If you don’t enjoy it, then it’s useless. I know a lot of people who really want to be famous or whatever, but they don’t really practice the guitar., They think all you do is grow your hair long and look freaky and jump around, and they neglect the musical end. It is tough to learn music; it’s like having to go to school to be a lawyer. But you have to enjoy it. If you don’t enjoy it, forget it.”

Asked about his plans for the future, Eddie Van Halen answers, “Man, just to keep rocking out and playing good guitar!”